How an imprisoned immigrant is fighting to empower the wrongfully incarcerated

March 18, 2022

(Part two of a two-part series. Read part one here.)

At Rikers Island, as Prakash Churaman cycled through losing and regaining faith in life, and in his ability to prove his innocence, he found religion, converting to Islam in 2016. With his friend Ehsan, he recited the shahadah, declaring his exclusive belief in Allah. Every day, he prostrated his body in prayer. During Ramadan, he fasted. And every week, he attended the prison’s Islamic services.

The rhythm and ritual gave him structure and a sense of discipline. In the African American “old-timers” at the jail’s makeshift cinderblock masjid, who gave him advice and looked out for him, he also found affiliation with something larger than himself—an alternative and more hopeful belonging than the Bloods or the Crips could provide. These older Muslim brothers spent much of their time at the law library.

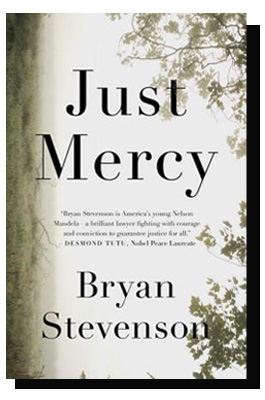

Prakash became a regular there, too. He exploited every resource in the library that might help him strategize a way out. He read Just Mercy, a memoir later made into a Hollywood movie, narrating public interest lawyer Brian Stevenson’s crusade to defend prisoners on death row and the wrongfully incarcerated through Alabama’s Equal Justice Initiative. To fire his will to fight, Prakash turned to the book repeatedly, as to a sacred text that revealed mass incarceration as the new Jim Crow. He also religiously studied Connections, a directory of community-based organizations and other resources for people in prison published by the New York Public Library.

“I was forced,” Prakash explains, “to … grasp the awareness and the knowledge that present[ed] itself to help me fight for my life.”

He used the contact information in the guidebook to begin a tireless campaign to plead his case. He wrote to and cold-called universities, law firms, law clinics, the local TV news station PIX11, even one of the men wrongfully convicted in the Central Park Five case, Yusuf Salaam. From the elders at the law library, he was learning that “the same laws, the same tactics utilized by the government against us can be used against the government.” With skills gained through a seven-week course in legal research at Rikers, he turned to case law, which he searched using electronic tablets available at the library, to aid in his own defense.

Ultimately, he also earned his GED while in jail. Although a psychologist who evaluated him at Crossroads had found his IQ low enough to indicate a mild intellectual disability, Prakash pursued every opportunity provided to educate himself, and he became an articulate advocate for himself.

“Jail did that to me,” he reflects. “I was really forced to survive off of pen and paper and stamps and a few-minute jail calls a day.”

Frustrated by his court-appointed attorney, he also started filing motions on his own behalf. One, in early 2017, asked that the judge recuse himself from the trial because, after thirty years as a career prosecutor, he couldn’t be fair or impartial. Two months before turning eighteen, and three days after New York Governor Andrew Cuomo signed an order that all juvenile defendants be tried in family court, Prakash petitioned the court to transfer his case there. In his thirty-seventh month of pretrial detention, in early 2018, he petitioned the court to release him because he’d been denied a speedy trial.

“The people are procrastinating,” he wrote. “My innocence will be proven, and I’d have a better chance to prove it if I was out.”

The path out was cut with the help of a succession of allies beyond bars, committed to systemic criminal justice reform.

The catalyst was Jacob Cohen, a cellist in his mid-thirties transfixed by the confidence and creative potential of people incarcerated ever since he was a freshman at Bard, teaching GED through the college’s prison education program. After the suicide of a former pretrial detainee at Rikers, held in solitary for years, sparked an outcry for reforms, Cohen was hired to perform as part of a program that brought the arts into the jail. For six hours a day, five days a week, he played the cello, often in the unit where unruly prisoners were sent as punishment.

That’s where he met Ehsan, whose personality exerted a gravitational pull, and Prakash, the reserved sidekick in the orbit of the other’s swagger. In that unit, the audience was tough and sometimes sharp-tongued with their skepticism, but Cohen’s improvisational style, amplified by the cement walls, captured their attention. Ehsan christened him “Cello,” the nickname a mark of inclusion in the social world of the jail. Eventually, the curious were asking for lessons, and the more expressive were irreverently freestyling with Cohen, some even composing original lyrics in the moment or for Soundcloud.

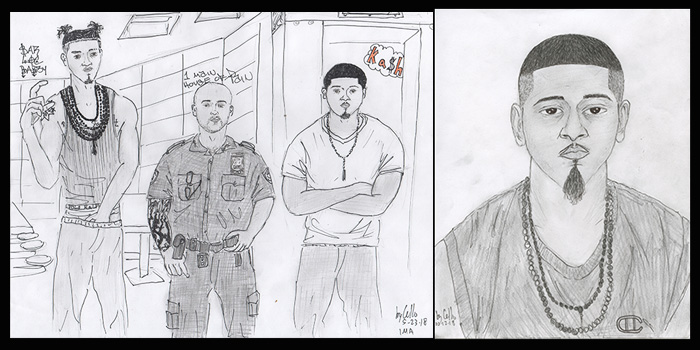

The days the music didn’t work, he created ink portraits of the inmates, teaching himself to draw as he went, learning to render hands by sketching gang signs and developing relationships with his subjects. He printed hundreds of the images that he created in a serial underground zine, Impressions of Incarcerated Youth, which he took from unit to unit, letting the young people leave comments as if it were an analog form of social media.

Cohen’s many portraits of Prakash—trying a bow against the cello’s strings, doing pushups, striking a tough-guy pose with Ehsan and a corrections officer, sitting with his eyes downcast and his hands folded, the knuckles raw—depict a brooding young man. When Cohen first met Prakash, he had been locked up for two and a half years and had minimal contact with his court-appointed attorney.

“He was lost at sea with no support,” Cohen recalls. “He needed help real bad and nobody was giving it to him.… A lot of kids who have those serious charges do not have paid lawyers. They’re just getting railroaded, completely. I would have helped any one of those kids. They’re all poor people of color that have no resources.”

His years working with thousands of imprisoned young people at Rikers showed him a punitive, dehumanizing system that, rather than rehabilitating them, trapped them in a self-fulfilling cycle that erased them from society. “They go in kids, and they come out gang-affiliated killers,” he says. “Most of these people go in and become highly traumatized. Most of them already were from the jump. From the day they were conceived, their life has been fucked up. You go from broken home to the group home to the juvenile facility to Rikers Island to prison.”

Cohen was, as he puts it, “raised with prison reform in the forefront of my life.” His parents, who met at a Bay-area Das Kapital reading group, have both worked with the incarcerated. His father, a medical director for juvenile justice facilities in New York State for two decades, once had a Rikers nickname, too: “Sick Call,” from his time doing rounds there as a medical resident, the year Cohen was born. His mother, an entomologist, became a lawyer to help exonerate a man she met while teaching in prison, and she later became legal adviser to the New York Senate’s corrections committee.

Influenced by her example and impressed that Prakash continued to refuse a plea deal, Cohen agreed to help him. A year after they met, Prakash came to him with a specific ask: a YouTube video to raise the fees for a lawyer and private investigator to mount a robust defense. “Innocent Since 15” splices together Cohen’s jailhouse sketches of Prakash with childhood photos and a minute-long audio clip, his earnest appeal during a phone call from Rikers. In a still-impressionable voice, the accent bearing marks of New York, the teenager declares, “It’s hard to be innocent and poor at the same time.”

But before the video could circulate widely, it became moot as Cohen spread the word about Prakash through more traditional channels, old-school networks of educated elites critical of the structural racism of the criminal justice system. The tale of the disadvantaged Guyanese immigrant, with his lack of social and financial capital, made its way to a party in Brooklyn, where recent NYU law graduate Rhiya Trivedi heard it from a horticultural therapist at the jail, her best friend from college, a selective private school in New England. Trivedi had recently started working as a junior partner with the attorney Ronald Kuby, mentored in defending radical and unpopular causes and clients by the renowned, late civil rights lawyer William Kunstler.

Cultivating a colorful style in the courtroom, with his silver ponytail and wisecracking cross-examinations, Ronald Kuby is an eccentric, recognized figure in New York social circles, the subject of two lifestyle profiles in The New York Times. Once co-host of a popular radio show on WABC-7, sparring every morning for more than a decade with Guardian Angels founder and recent mayoral candidate Curtis Sliwa, a conservative, Kuby is a regular commentator for Court TV and local broadcast news in New York City.

He’s so well-known that, when he took Prakash’s case to trial, several potential jurors were disqualified because they knew and thought they might be influenced by “his notoriety.” He has defended members of the Gambino crime family, Occupy Wall Street protestors, and the Hells Angels. Unabashedly political, he and Rhiya Trivedi have handled several First Amendment, false confession, and wrongful conviction cases, including the appeal of one of the Central Park Five and the defense of a woman who climbed the Statue of Liberty to protest Trump’s family separation policy.

Trivedi, who describes herself as a prison abolitionist, was moved by Prakash’s case, especially his claim of coercive interrogation tactics. The daughter of South Asian immigrants, from an upper-caste Hindu family whose privilege and politics she disowns, she was also touched by his family’s ancestral roots as indentured plantation laborers. She expressed interest in taking his case pro bono. When Prakash called Trivedi and Kuby from Rikers, in the summer of 2018, he told a story he would go on to recite publicly countless times in the coming years.

“We love any particularly righteous fight. The more we talked to him, the more we became interested,” recalls Trivedi. “He was young. He’d been in custody for a very long time. They’d stolen his childhood from him.”

When Kuby and Trivedi decided to represent him, Prakash’s legal case moved swiftly, proceeding to trial in just three months, after almost four years of inaction. Ehsan remembers Prakash going to court in his suit and tie, “feeling sophisticated, looking sophisticated,” and “coming back with mad paperwork,” staying up until one a.m., studying his case file, “hope in his eyes for the first time.”

During the trial, Kuby argued that the detectives who questioned Prakash used tactics that made his statement unreliable. “What they did was they fed him the story piece by piece and had him repeat it,” he told the jury. He portrayed Prakash as a scapegoat, “stray” and “outsider” who supplied police the narrative they wanted because they applied psychological pressure, partly by leveraging “the threat—what is your father going to do to your mother when he finds out about this.”

They lost the case, and Prakash was sentenced to nine years to life and sent to a maximum-security prison in upstate New York.

But a year and a half later, in June of 2020, they snatched the potential for victory from the jaws of defeat, with a successful appeal. During trial, the attorneys had offered an expert witness on interrogation techniques common to false confessions involving juveniles, but the judge, Kenneth Holder, did not allow the testimony, stating that the average juror understands what coercion is, without expert guidance.

The appeals court, in overturning Prakash’s conviction and ordering Holder to retry the case, ruled that the jury should have heard the expert’s testimony. Prosecutors then offered Prakash a deal: If he pleaded guilty to a lesser charge of assault, he would receive a significantly reduced sentence, with time served, and would now be free. He refused, against the advice of Kuby and Trivedi, prompting them to withdraw from the case.

Sent to Rikers without bail to await his new trial, and without a star legal team, Prakash remained undaunted. He traded food in the commissary for allotted phone time from those who had no one to call, to maximize his minutes. His strategy was “food for phone calls,” he says, “to communicate with the outside world, one of the only resources I had.” And he expanded his list of contacts to call regularly to plead his innocence.

He called Julian Guerrero, a former political organizer and the cofounder of Working Class Heroes, a socialist podcast broadcast on WBAI radio that launched just a few months before Prakash returned to Rikers. Hearing the podcast’s segment on Covid-19 and the courts, and its invitation for people in prison to call in, Prakash left a voice message, asking the collective that creates the podcast to feature his story. Persistent, Prakash rang Guerrero almost every day, seeking his help as narrator and as organizer. “That insistence on his own self-worth and dignity is what has propelled him through this entire process,” Guerrero says. “Prakash knew that if he didn’t get his story out there and if he remained voiceless within the criminal justice system, he would not really get a fair trial at all.”

Ultimately, Guerrero and his team produced three segments on Prakash that helped build a movement to campaign for the Queens district attorney, Melinda Katz, to drop the charges against him. With the help of Desis Rising Up and Moving (DRUM), a Queens-based group that advocates with and for working class South Asians and Indo-Caribbeans, Guerrero also organized a rally in front of the Queens Criminal Courthouse on the sixth anniversary of Prakash’s arrest to press for bail.

In his own push for that, Prakash also regularly called a volunteer with the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee, now known as Root and Branch, who had helped Prakash’s cellmate at Rikers win bail. Prakash developed a relationship with the organizer, a comparative literature graduate student who had worked with incarcerated youth in New Jersey as an undergraduate at Princeton. “I can’t free them all,” said the organizer, who asked for anonymity out of fear of being barred from prison visits. “I can’t be a savior like that, but Prakash being someone I felt I knew very well…”

When the court did grant him bail, a week-and-a-half after the courthouse rally, it was this volunteer who secured $15,000 in cash from the National Bail Fund Network. He and Guerrero both also recruited friends and family to co-sign, along with Prakash’s uncle and father, to guarantee the remaining $135,000 if Prakash skipped bond.

And, of course, he continued to call Cohen, who believes he lost his job at Rikers because of his advocacy for Prakash and who remained in close touch with him while he was imprisoned upstate. After the courthouse rally, Cohen set up and ran an Instagram page for the Free Prakash Alliance, the ad hoc coalition of his newfound allies and supporters, built on a community defense model for empowering the wrongfully incarcerated. They mobilized to circulate a petition calling for his exoneration and a GoFundMe page to raise money for bail before the National Bail Fund Network stepped in. Because secure housing was a condition of his release, the $20,000 initially raised was used to cover half a year of rent for him and his mother, who had just lost her job and apartment.

The two Indo-Caribbean organizers with DRUM who helped the family find rooms in a house in Queens brought to their relationship with Prakash their own flashbacks of being arrested and, they say, ethnically profiled by police. “I still have nightmares from my own moment,” says Will Depoo, who recounts being picked up by police on a Queens subway platform when he was seventeen, interrogated about a crime he knew nothing about, and called a “coolie,” a slur for Indians descended from indentured plantation laborers, before being released without charge.

Now an organizer with the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development, Depoo in his time at DRUM had to contend with a paradox: a significant number of Guyanese serve as New York City police officers, but Guyanese were targeted for special surveillance after 9/11 as one of twenty-eight “ancestries of interest” by the New York Police Department’s now disbanded Demographics Unit, along with immigrants from predominantly Muslim countries in the Middle East, South Asia, and Africa.

After his release, Prakash became an active member of DRUM, producing a testimonial video for the organization as part of its campaign for politicians to defund the New York City Police Department, and instead invest in job training, educational, recreational, and other community resources.

Guyanese make up the second largest immigrant group in Queens and the fifth largest in New York City. The judge trying Prakash is the son of a Guyanese immigrant, and the juror who complained to him of being bullied for deadlocking the jury is also an immigrant from Guyana. The former British colony in South America stretches across a largely unpopulated land mass the size of New Jersey, with fewer than a million people, mainly the descendants of enslaved Africans and indentured South Asians; but for decades, it has had an outsized impact on the demographics, workforce, and cultural fabric of the city.

In an opinion piece for The New York Daily News, calling on Katz to drop the charges against Prakash, a Guyanese American corporate lawyer and board member for the South Asian Bar Association of New York, whose brother died in the custody of New York police, noted: “Guyanese in New York are both underserved and overpoliced.” In another show of support for Prakash, a Guyanese American who serves as senior legislative counsel to the New York City Council stepped down from her position on Katz’ South Asian and Indo-Caribbean Advisory Council. A Guyanese American audio producer for Random House interviewed him for Cutlass, a podcast aimed at Indo-Caribbeans across the globe. This past fall, several Queens politicians of South Asian origin, including two newly elected city council members and a state assemblyman, echoed the calls for Katz to drop the charges in a letter co-signed by Congresswoman Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez and more than a dozen other federal, state and city lawmakers.

“What’s working for Prakash,” Guerrero observes, “is that he has a community movement around him that is able to leverage pressure within civil society, on the criminal justice system, on the DA, on local pols to do something, to say something to bring attention.… He’s reaching out in a way that builds solidarity.”

Prakash has used the past year out on bail not only to assert his own innocence, but to criticize vocally the system that schooled and incarcerated him, others like him, and others not, on the surface, like him. Reaching outside the Guyanese and Indo-Caribbean communities, to African American, Afro-Caribbean, and Latinx communities, he’s given a platform at his rallies to the families of others who claim coerced confessions and police misconduct, such as the mother of Chanel Lewis, the teenager serving a life sentence for the rape and murder of a jogger in Howard Beach, who was interrogated by one of the detectives who questioned Prakash and is also the focus of a wrongful conviction campaign.

Prakash has also lent his voice to the group How Our Allies Link Together (HOLLA), devoted to empowering young people of color, especially those in the seven neighborhoods in New York City that have historically accounted for the majority of incarcerated people in the state’s prisons. The neighborhood where Prakash sometimes slept in the park, Jamaica, is the only Queens neighborhood among the seven. At a webinar that HOLLA hosted, he called for recreation centers and for workshops to educate young people about their legal rights, to fight against aggressive policing and avoid his fate.

His evolution into an activist has impressed Cohen, who produced the Instagram video “The Prakash Churaman Story,” for the ways that Prakash has transcended the systems that have traumatized him. “The amount he’s changed, from this quiet, shut-down kid to now he’s so confident making all these decisions,” Cohen reflects. “He has agency in his life.”

The intersectional coalition that Prakash has built includes the Party for Socialism and Liberation, the East Harlem-based community organization Justice Center en el Barrio, and an organization campaigning to end solitary confinement in New York. The individuals who have rallied around him include an eighteen-year-old studying criminal justice at John Jay College, a public school aide who immigrated to the United States undocumented as a child, a medievalist-in-training at Columbia, an illustrator from South India who is a prison abolitionist, and Zion the 83rd, a record producer and creator of genre-defying underground music who produced a three-minute video about Prakash, “Exonerated,” that went viral on social media. They’ve showed up to his courthouse rallies and at protests outside Katz’ office, leafleted for him in the Guyanese enclave in southeast Queens, and conducted weekly phone zaps to the prosecutor handling his case. They also showed up for him on his birthday, at a backyard barbecue for the 4th of July, and for a gender reveal party for his baby.

“That community brings hope. They bring friendship to Prakash,” observes Guerrero, who was an early member of the Free Prakash Alliance. “They bring a team of people who allow him to brainstorm ideas. He’s learning things right now that it took me ten years to learn, about how to organize, and he’s getting it all in a couple of months. … This whole process has also been a political education for Prakash and for me too, for everyone involved.”

In the two-bedroom apartment where Prakash has lived with his mother for the past year, on the ground floor of an eggshell white clapboard house tucked in an industrial area in the floodplains of a bay, he gravitates to the door. Pacing at the threshold, an electronic bracelet on his ankle, he’s caught between two states of being. Sometimes hopeful, he calls where he is “pre-freedom.” Sometimes frustrated, he says, “I feel like I was just moved from one cage in jail to another cage in society.”

Confined to the house, except for court appearances, medical check-ups, and weekly visits to a therapist at the Fortune Society, Prakash calls the sheriff’s office daily to check in. Because he can’t leave the house, he can’t get a job. He hopes one day to become a paralegal or perhaps to start a business embossing t-shirts protesting wrongful incarceration. For the moment, however, he finds it difficult to sit still, to focus on a page long enough to read, to focus on anything really but his legal case.

“My life is stuck,” he says. “I wake up every day and the only thing on my mind is my trial.… I feel like I’m running in circles with the system. When is it going to be over?”

Alert to the cars with tinted windows that roll by, which he believes to be part of the official surveillance of him, he is watching as much as he is watched. Outside the house, he has trained five cameras, installed after he received death threats, and he monitors them from his cell phone. The persistent low boom from planes departing from an airport nearby mock his own inability to take off. Underscoring the irony, the sheriff’s office called to warn he was in danger of violating bond whenever his ride home from the doctor’s office or courthouse approached exits to the airport.

Suspended between immobility and agency, faith and pessimism, he’s facing a new trial before the same judge as early as next month. With the help of Jose Nieves, a court-appointed attorney who ran against Katz for district attorney and who won him bail a year ago, he remains adamant: “I refuse to bow down to the system. I will continue to say that, ‘cause I will continue fighting.”

Newly a father, he has an intensified and renewed will to prove his innocence. His girlfriend, who met him at one of his courthouse rallies after hearing him tell his story to a Guyanese reggae artist on Facebook Live, gave birth to a son in December. Through his baby, his legacy now exists in the flesh, but he also wants to lend his name to a law in New York to require that an attorney always be present when a juvenile is interrogated.

“I want to make a change,” he says. “I want to be someone. I want to be remembered. I want my name to live on even when I’m gone.”