“Indonesian literature is gaining traction. More slowly than we might want, but it’s an upward trajectory.”

July 8, 2020

Indonesian author Intan Paramaditha spoke with Stephen Epstein, winner of a PEN/Heim Translation Grant for his work on her novel The Wandering (Harvill Secker/ Penguin Random House UK 2020). In this follow-up to Apple and Knife, Paramaditha has written a playful choose-your-own-adventure novel on the highs and lows of global nomadism, the politics and privileges of travel and desire, and the results of our choices. The below digests their chat about Stephen’s experience working with the Korean and Indonesian languages, the challenges of rendering The Wandering, and the future of translation for Southeast Asian literature.

◻︎◻︎◻︎

Intan Paramaditha: We’ve known each other since 2011, and you’ve translated my story collection Apple and Knife (2018), and my novel The Wandering (2020). I’m very grateful for our encounter, which wouldn’t have happened without your passion for languages. You have a Harvard BA and Berkeley PhD in Classics, and as a scholar you’re known for work on Korean society and popular culture. But you also translate fiction from Indonesian. That’s a journey some might find hard to imagine.

Stephen Epstein: Well, my career has definitely involved a journey that spans decades. For some it might be hard to imagine, but for me there’s a clear logic in that I’ve always been fascinated by languages, literature and other cultures. Anthropologists often work in multiple sites over the course of their careers; I’m just doing it from slightly different disciplinary perspectives.

IP: Can you tell us more about how you became a translator?

SE: Back in 1986, when I was in grad school, studying ancient languages, students at Berkeley mobilized to have a course offered on Korean literature, which immediately grabbed my attention. I had a lot of Korean-American friends, and had transited through Seoul the previous summer during a trip to visit former roommates working in Japan and Taiwan. My day there convinced me to return the following year for a more extended trip, and I’d already started studying Korean with a tutor.

The course itself was great. It was led by Marty Holman, who’s primarily a translator of Japanese fiction but also worked on Korea. Everybody was really engaged, and the readings were fascinating. Marty was then putting together anthologies of stories by the author Hwang Sun-won, whom we read a fair bit of and whom many consider Korea’s finest short story writer. The father of one my closest friends had had Hwang as his Korean literature teacher in high school, so that gave me a sense of personal connection.

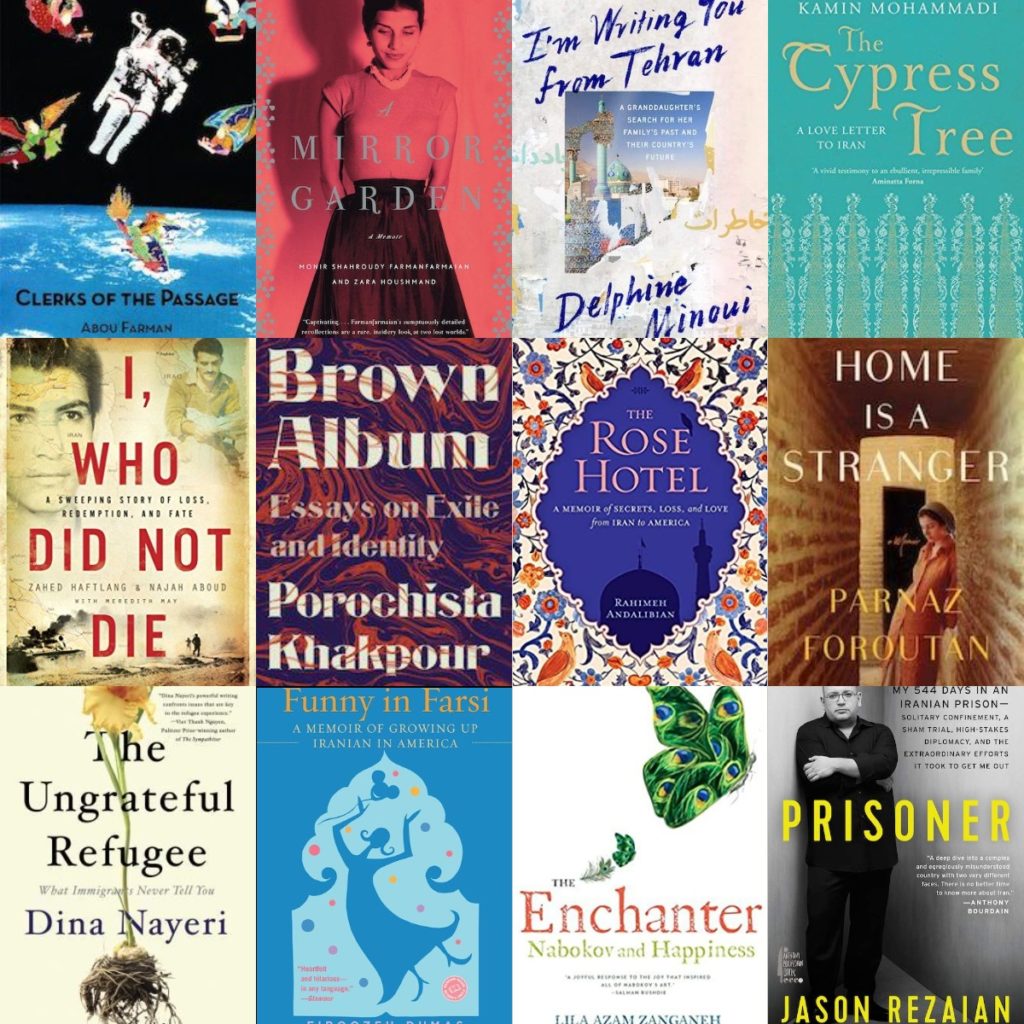

Issues of translation came up regularly in the class, and they really intrigued me, since I was training as a classical philologist, which essentially involves fine-grained analysis of words in context. Even though we were reading great stories, the translations themselves were pretty uneven. Korean literature in English has developed terrifically in recent years, with translators like Sora Kim-Russell, Kim Ji-young and Deborah Smith, who won the Man Booker International Prize for Han Kang’s The Vegetarian, but many pieces we read then hadn’t been translated by native speakers of English, and were clunky and wooden, often not even grammatical. I thought, well, even if I never master Korean, I can produce more readable text than much of what was available. I threw myself into the language and wound up spending a year at Yonsei University to study Korean intensively in 1989-1990, after I’d finished all my PhD exams but before writing my dissertation, in the hopes of getting to the level of being able to translate.

IP: So you learned Korean and started translating before it became hyped.

SE: Oh yeah, long before South Korea became cool. It was purely a labor of love at that point. But I can’t imagine that a single person in the late ‘80s, as the military dictatorship was being dismantled, would have predicted that South Korea would be one of the world’s key producers of pop culture in music, film and TV drama by the 2010s. I’d have been more inclined to predict that its literature would have drawn attention first, actually.

IP: Were the works you’d read in the course published by Korean or American presses?

SE: Mostly Korean. In the ‘80s UNESCO had a publishing company based in Seoul called Si-sa-yong-o-sa, which was the source of a lot of what we read. We used a smattering of other texts, including Peter Lee’s anthology Flowers of Fire on University of Hawai’i Press, which was definitely a cut above. Few presses were interested in Korean literature at that point, but Marty’s anthologies came out with Readers International from the UK and Mercury House in the US, and I wound up contributing to both.

IP: How did you end up translating Indonesian literature?

SE: After my program at Yonsei, I had two months to travel before returning to Berkeley and went to Malaysia and Indonesia. I was enthralled by Indonesia immediately. The people were great, the food was terrific, the cultural diversity was amazing, and the landscape blew me away. I made my way across Java, skipping from one volcanic upland area to the next, climbing as many as I could. I’d started studying Bahasa Melayu before leaving the US and found it a really compelling language. After wrestling with Korean, it was refreshing to work on a language that is much easier for native English speakers and to develop conversational ability pretty quickly.

IP: So your interest in Indonesia began with your own gentayangan/ wandering experience.

SE: Very much so. My own gentayangan. Back at Berkeley, I sat in on courses with Amin Sweeney and Sylvia Tiwon. In Sylvia’s class, we read short stories by Pramoedya Ananta Toer. I also had my first intro to Putu Wijaya, whose work I’d later translate. The library had an edition of Putu’s short stories with a facing translation produced by Ellen Rafferty. I loved his wild imagination and critical eye, and the facing translation helped me build up my vocab and reading speed. I must have read that volume three or four times.

In the following years, I visited not only Korea but Indonesia whenever I could—trips to Sumatra, Sulawesi, Nusa Tenggara, and back to Java twice. I kept up with the language, listening to BBC Indonesian once the Internet made it possible, and reading more literature. My experience with Korean made me keen to try translating some Indonesian fiction too. I’d particularly liked the short story “Becaaak!” by Marselli Sumarno and that wound up my first Indonesian translation, back in 1998 in Indonesia magazine. When I felt confident to try something longer, I began working on Putu Wijaya’s novel Telegram, although it took me almost a decade to see into print, with other projects getting in the way.

IP: Which is easier, translating from Korean or Indonesian?

SE: For me? Indonesian, definitely. Indonesian sentences are generally shorter and clearer, and I usually get a working draft on the first pass. Korean is grammatically and syntactically different enough from English that even getting a passage to sound idiomatic while capturing the original can be a challenge. And that’s before you start to think about polishing for a literary quality.

IP: Apple and Knife has a long history. In 2015, Indonesia was the Guest of Honour at the Frankfurt Book Fair, and BTW Books produced mini-books of Indonesian authors in Indonesian, English, and German. You translated four of my stories, and then a larger collection. What was the idea behind it?

SE: Well, I really liked your work! I knew John McGlynn from Lontar, the publisher that has done the most to bring Indonesian literature to outside audiences. John was regularly looking for translators and he’d invited me to translate your story, “Spinner of Darkness” for a Lontar volume and then to be the English translator for the BTW edition. I’d enjoyed it so much that I wanted to do a fuller anthology and also believed it’d attract interest.

I suppose another factor was that though we hadn’t yet met in person, we’d had lots of email contact and your level of English and background as an academic made working with you easier and faster than with other authors, and I felt like we were on the same wavelength. As a translator, it made it easy to respect your work while exercising creativity, because I knew I’d get great feedback on it, and our discussions were always interesting.

IP: Did you think about the challenge of finding publishers, especially for a short story collection?

SE: Not so much. I thought that since we’re both in Oceania your work might appeal to an Australian publisher. It took some time, but we eventually (and fortunately!) wound up with Brow Books and a wonderful editor in Elizabeth Bryer, who translates Latin American fiction herself.

IP: Yes, a book is always a collaborative process, though not to the same degree as film or theatre. The roles of the translator and the editor are crucial.

SE: I learned so much from Elizabeth and her suggestions to you, and your openness to being edited freed up my own creativity in translation further. It became even more of a team process, with the goal of getting the best book possible in English.

IP: What made you decide to translate The Wandering?

SE: Oh, easy. After the great experience with Apple and Knife, I wanted to continue the collaboration. And I loved working on The Wandering too.

IP: Was translating The Wandering more difficult? Did the “choose-your-own-story” structure create an obstacle?

SE: One thing I love about your work—and especially The Wandering—is your care in structure. The choose-your-own-adventure motifs creates difficulties, in keeping on top of details and ensuring that readers have a smooth experience, but as a single text that I came to know deeply, instead of grappling with multiple short stories, The Wandering was also easier in some ways. I tried to bring out different voices in English to convey variations from thread to thread, while seeking an overarching unity.

For my first draft I went through page by page, even as the narrative was diverging. I do feel that was the best strategy, but on a later full edit, I went through each storyline, one by one to make sure they all cohered. The Wandering is a risky book because of the way it engages readers with choices that mean everyone’s experience of the text is different.

Its complexity also demands that readers be patient and go through each thread to grasp the novel fully, but if readers are just after some narrative conclusions, they can go through a few storylines and put it aside. I think that makes The Wandering a much more cerebral experience than Apple and Knife, which is more visceral. I really loved that about the novel. I think the level of personal resonance in The Wandering may have helped too.

IP: As a traveller?

SE: Yes. The travel motif and its attention to the existential question of how decisions can set us on different life paths, a topic I’ve often dwelled on. One area of resonance but discomfort was dealing with the character Bob. Not often I have to deal with characters who are Asian Studies professors! I’m also very much not Bob, but having a character I intersect with was a new translation challenge, especially because of how our work involves a close collaboration than other authors I work with, and more of my input.

IP: I’ve felt like your suggestions are crucial to the translation. Given your experience of Bob, do you think translators need to relate to a text’s characters? Can you relate to the second-person “you” in the story?

SE: Yes, although “you” is obviously very much not me. I suppose in a similar way that I can see intersections with Bob, “you” both draws on you and is very much not you. I liked “you” in the book, her intelligence and cynicism, but I don’t think a translator necessarily needs to relate to characters.

That said, some form of narrative identification makes the process more enjoyable. One Korean novel I translated had characters I didn’t particularly like, and that probably made the experience less fun. You become involved in the text differently, but I don’t know how much it affects translator decisions. Or put it this way: if you don’t like characters you may engage in word choices that make them less likable, but that is part and parcel of every translation being an interpretation. It would be an issue if you feel that the author wants a character to be liked and that you’re wilfully misrepresenting the original.

IP: As a translator and traveller, how important is location? Do you need to be to be immersed in the environment where the language is spoken when you translate?

SE: Well, it definitely helps to have a sense of a novel’s setting to visualize things. For The Wandering, it was probably more important that my sister lives in Queens, NY where much of it is set. But linguistically it helped me to be in Indonesia during my edits, primarily to speed up my final re-reading of the original.

IP: Only three percent of books published in English are translations, and this pool is dominated by European languages. How do you view this as someone who champions Asian languages and literatures?

SE: I think over time there’ll be more literature from Asia in English. Korean lit’s journey from little-known to global leaves me optimistic. My optimism may also reflect teaching in a university that houses the NZ Centre for Literary Translation and has a burgeoning literary translation studies PhD programme. Literary translation is recognized here as an important scholarly activity.

IP: It’s good to hear of universities with literary translation studies. But in the wider publishing industry and reading culture, changes are slow. Last year I went to Jakarta’s international literary festival, a South-to-South festival that allows writers from Asia and Africa to interact. Thai author Prabda Yoon mentioned that not one piece of Thai literature is well known globally. This is changing because his own books and Duanwad Pimwana’s, also translated by Mui Poopoksakul, have started to attract attention. But sustainability is an issue. Unlike South Korea, Southeast Asian governments provide little support for translated literature. The effort comes from translators and small publishers both in the country of origin and Anglophone countries. Can Southeast Asian literatures become more visible globally? Though of course the category of ‘global literature’ itself raises questions because what its parameters are mainly defined by Anglophone gatekeepers.

SE: It’s an uphill battle, but I think they will. Indonesian literature is gaining traction. More slowly than we might want, but it’s an upward trajectory. A viral boost can come out of the blue these days. I don’t know how much of Korean lit’s success should be attributed to government support. I want to believe more in readers and the public. Of course, support helps, and government agencies can connect authors with agents and publishers, and offer subventions for book tours and publicity. And I believe there are more talented translators available to bring Southeast Asian lit into other languages than ever before.

IP: I do too. For Indonesia, I’m excited about the translations of Tiffany Tsao, Khairani Barokka, and Eliza Vitri Handayani. Eliza initiated Intersastra, a platform featuring translations by talented young Indonesian women like Madina Malahayati Chumaera and Shaffira Gayatri, which Tilted Axis Press has been advocating this through their project Translating Feminisms. We need more platforms promoting literature from the Global South, written and translated by women!