Im lặng nhẫn nại của vực sâu hối thúc tôi mở mình | The patient silence of the abyss urged me to open myself

April 30, 2021

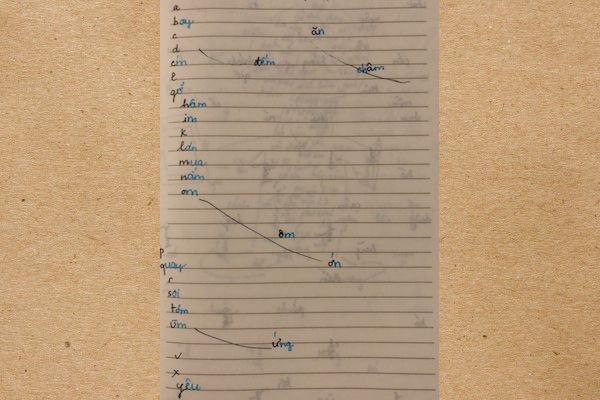

Editor’s note: Today’s essay by Nhã Thuyên, translated by Nguyễn-Hoàng Quyên, is the final piece in a notebook of experimental and experiential Vietnamese writing, the collection of which is gathered here. The pieces of this notebook, having transformed across time and space as well as various material forms, are presented here in their digital bodies as reproductions of the print edition tôi viết (tiếng Việt) | i write (in Vietnamese) (AJAR, 2021) and its art exhibition in Hanoi. We encourage readers to click on any images of text for enlargement. Print copies of tôi viết (tiếng Việt) | i write (in Vietnamese) are available for purchase here.

Click here to read the English translation by Nguyễn-Hoàng Quyên or scroll to find it below

những tiếng

(Xuất bản lần đầu trên tạp chí Tia Sáng (2017) và đăng lại trong ấn phẩm Măng Ta (Thu 2020), bản dịch tiếng Anh xuất bản lần đầu trong tuyển tập các sáng tác từ châu Á Thái Bình Dương The Near and the Far của nhà xuất bản SCRIBE, Melbourne and London, 2019)

Tiếng tôi, lòng giếng Việt

Viết, thuở lên ba lên năm, tôi vẫn còn mường tượng lại mình, tay cầm viên phấn, mẩu que, lồm cồm nền đất, sàn nhà, thẩn thơ bên cánh cửa, tủ hàng của mẹ, nguệch ngoạc những nét đầu tiên, chép đồng dao, vẽ tên người quen kẻ lạ. Tôi đã thích trò chơi giao tiếp đó, thú cái phương thức bỡ ngỡ nối một đứa trẻ biết đọc, biết viết từ sớm với những người lớn nhọc nhằn sống và chỉ còn chút niềm vui nhìn những đứa trẻ lớn lên. Nhưng khi đứa trẻ-tôi lớn lên, viết, dần không còn là để tỏ bày, để mở ra, để nói chuyện với, mà trái lại, để che giấu, để gói lại, để giữ im lặng. Tôi, với giấy mực và trí tưởng non nớt, lấy lẽ “bận viết”, những chỉ muốn bọc nỗi một mình, lơ là tiếng mẹ gọi, tránh đối mặt, giấu nỗi sợ phơi bày, và mộng những thế giới tôi chưa từng đến. Hân hoan lẫn sợ hãi, tôi cảm biết chữ nghĩa đang lắng nghe, trò chuyện, chơi đùa với tôi, tôi mơ hồ thấy mình cúi nhìn bóng mình trong lòng giếng, một cái bóng xám sánh màu nước thẫm in nền trời, và nỗi tôi tò mò run run trước độ sâu lòng giếng phiêu dạt cùng các tích truyện cũ, men theo vòng tròn những lời nguyền dưới đáy.

Im lặng nhẫn nại của vực sâu hối thúc tôi mở mình.

Cái nghịch lý của viết từ đó đeo bám tôi: kẻ tưởng được giấu bị lần qua những tàn chữ vãi vung vở nháp, những mảnh giấy vụn ủ bụi hộc tủ, ngăn bàn. Một chốn nương náu bày ra, những chữ phơi bày chính chúng.

Tôi có thể nào tránh bị-được đọc, bị-được phát hiện khi tôi đã viết, và tôi đã, một run rủi nào, làm lộ ra, và hơn thế, mời mọc những kẻ lạ bước vào chốn nương náu ấy.

Không đường lui, tôi phải tự vượt qua nỗi sợ bị kẻ khác thấy và chạm tới. Tôi học cách bình tĩnh hơn với đôi tai midas của mình, mở tai nghe những thì thào của cây cối, đất đai, những kẻ khác. Và dẫu không lúc nào thôi rụt rè, đôi khi sợ hãi cụp chặt lại, đã thấy tôi bớt xa lạ với người khác, hay bớt xa lạ với chính mình, và tôi muốn yêu nỗi xa lạ ấy. Tôi đã thôi kháng cự, trừ kháng cự việc dừng lại, bởi nỗ lực mở lòng luôn là một nỗ lực hàn gắn và hiện hữu, một

nỗ lực chưa biến mất quá sớm.

Tôi náu trong tiếng Việt như nép dưới một tấm mền, một tấm khiên, một lớp màng bọc, hay có thể, lúc nào đó, một lớp vải liệm, một cái nắp áo quan, hay tôi đã luôn ở trong tiếng Việt, cái bóng đứa trẻ náu trong lòng giếng.

Tiếng thơ, thứ tiếng khơi động phần tôi kín nhất, trở thành chốn tôi vun trồng, đùa chơi, thức ngủ, riêng tư và rộng rãi. Thơ tới từ đâu và làm sao tôi biết? Dưới lớp da, những từ ngữ trỗi lên trong những cơn đói giao tiếp đói nỗi một mình, đói một gần gặn một xa cách, đói một hiện diện một vắng mặt, đói một kết nối làm đầy tôi bởi những hiện hữu khác. Nhưng nhu cầu thơ hàng ngày là một nhu cầu lao lực: một đôi khoảnh khắc hân hưởng thuần lành nơi cảm quan tôi bật nở đổi lại bằng nhẫn nại khắc kỷ trong các bài học tiếng. Tôi đang phác hình một cách sống thơ hơn là nỗ lực chỉ làm ra các bài thơ: chung sống dẻo dai với chữ nghĩa, chăm nom những sinh thể chữ cọ quậy trong cơ thể bí bức đòi lớn dậy và sống đời sống của chúng. Tôi chăm chút tiếng thơ ấy: một thứ tiếng nơi muôn vẻ âm chữ cùng hiện diện và cựa quậy.

Có lúc, khi xông xáo, tự tin hơn, tôi đã nghĩ mình có thể dùng tiếng Việt, để diễn đạt mình, thuần hóa chữ nghĩa theo các ý tưởng. Bây giờ, tôi dè dặt học cách không dùng tiếng Việt. Tôi học cách nghe từ thở và đôi khi khẽ chạm những sinh thể chữ. Tôi học những bài học luôn là đầu tiên về tổn thương cũng như khả năng gây hại của từ ngữ, nơi tôi, kẻ học nói, học viết, luôn bỡ ngỡ, nín lặng những vết sẹo.

Tiếng dịch, một khung mở

Lòng giếng mở những khung trời. Chiều sâu này mở ra một độ rộng kia.

Tôi hàm ơn những người dịch trao tặng các trang viết tôi một biến thể đời sống khác, một thể nghiệm của đời sống gốc, một tồn tại song song. Bản dịch mời tôi một chuyến du hành, một cơ hội thoát khỏi tình trạng khô kiệt của việc ở quá lâu một nơi chốn, dò dẫm quá lâu trong đường hầm một thứ tiếng, nhìn quá lâu vào lòng giếng, như tôi đã cảm giác ở quá lâu trong tiếng Việt. Tôi cũng nghĩ nhiều hơn tới những kẻ viết chỉ còn nương bám

vào bản dịch để sống sót và tái sinh, khi bị từ chối, cắt bỏ hay giới hạn quan hệ đọc và khả năng sống ở tiếng gốc nơi quê nhà, bởi những may rủi của số phận, hay trong nhiều trường hợp, bởi những lưỡi kéo đáng sợ của một vài hệ thống kiểm duyệt văn hóa. Tôi nghĩ tới hiện diện bình đẳng của mọi tiếng nói và chữ viết, nỗ lực cất lời của những tiếng bị bỏ quên hay lơ là, hay bí ẩn thơ mộng của những âm chữ con người ít hoặc không có cơ may nghe hiểu. Tôi nghĩ về những xáo trộn không-thời gian qua của hành vi dịch: sự di chuyển các mảng sống từ nơi này qua chốn nọ, từ khung giờ này tới một khung giờ khác, những tồn tại xuyên không.

Hẳn nhiên, một bản dịch, cũng như bản gốc, có thể được đón nhận hay bị từ chối ở một miền thổ nhưỡng khác. Những người đọc giàu nghi hoặc vẫn ngờ một số tiếng thơ có thể dịch, hay người đọc có thể nghi ngờ thơ được đọc rộng rãi ngoài tiếng gốc của nó. Bản thân các tiếng dịch khác nhau cũng mang những hệ lụy riêng: một bài thơ dịch trong tiếng này đọc vào hơn trong một tiếng khác. Những thơ Việt nào có thể nhuần nhị trong các tiếng dịch?

Ta cảm giác khác biệt thế nào khi đọc Đường thi trong phiên âm và bản dịch tiếng Việt và trong tiếng Anh? Những khó thay thế và những bất khả dịch của một thứ tiếng thường được thơ bảo bọc kỹ lưỡng, và trong nhiều trường hợp, đó có thể là những điểm đáng giá nhất của thứ tiếng ấy. Và hẳn là có những tiếng, hoặc những người sử dụng tiếng, kháng cự quyết liệt xâm nhập của tiếng ngoài, dù là sự kháng cự bạo lực, hay chỉ như một tự vệ yếu ớt.

Nhưng tôi muốn nghĩ và trông đợi về những điểm va chạm và gặp gỡ, như trong tình yêu, nơi các tiếng nói có thể sẽ thôi kháng cự và có thể đón vào nhà những kẻ lạ, những người ngoài. Thơ, dù gắn chặt với bản gốc, tiếng gốc đến cỡ nào, tôi tin, luôn có khoảng rộng rãi cho những khả thể dịch, những khả thể băng ngang các tiếng và biên giới lãnh thổ.

Thực thì, cơ thể ta đang luôn sống và hít thở những tiếng dịch mọi nơi. Và có thể là thiết yếu để mở ra nhiều cách thấy và được thấy trong và qua các tiếng.

Tiếng đất, những rễ bật

Đất, một ẩn dụ mẹ, lo âu những cây không cắm rễ, những cây bật rễ, những rễ cằn, trơ khốc, không hợp đất. Bật rễ, trong tiếng Việt, luôn khó tách rời mất mát, bội phản. Ta nói mất gốc, dằn giọng một kết án bạo lực: một cái án đày, một cái án có thể dẫn đến thù nghịch, chối bỏ dữ dội.

Ngoái lại: một nỗi niềm Orpheus trả giá bằng bóng tối địa ngục. Có những kẻ, dù ra đi hay ở lại, dù bám đất nơi này hay di chuyển muôn phương, sống đời với nỗi căng thẳng đó: sự không thể không ngoái lại và sự không thể ngoái lại.

Tôi không nghĩ mình may mắn thoát khỏi những chất vấn của đất. Như nhiều người viết tiếng Việt đồng hành, tôi vừa muốn thôi bận lòng, vừa ôm giữ khư khư tiếng Việt, một tiếng, một chữ, một đất, một nước, một số, một phận, một thương, một vong. Như những người viết ở mọi nơi, tôi muốn được là một phần của cái bây giờ, cái nơi nơi, của đây luôn là của đó. Tôi muốn thấy tiếng Việt đồng hành với các tiếng khác. Tôi là một người Việt tự làm mình xa lạ trên quê hương, một người Việt ở đây và luôn dạt khơi xa. Tôi nghi hoặc sự tuyệt đối của tình máu mủ và những khái niệm căn cước. Tôi là một người lạ thân thuộc với những người lạ khác. Sự dần dần nhận ra về ranh giới và những tính chất Việt ở nơi này nơi khác đến cùng với sự dần dần nhận ra những xóa bỏ và đánh mất những tính chất Việt trong tôi. Có một nông nỗi bồn chồn: niềm tha thiết một miền đất ấu thơ và lựa chọn bật rễ, phiêu dạt, bỏ lại đằng sau những ngôi nhà, những lời hẹn ước, chưa ngoái lại, một chẳng đặng đừng có ý thức, hay một dồn đẩy của số phận, cả khi tôi vẫn đang đặt chân đây quê nhà.

Tôi là đứa trẻ lạc trong những sum vầy dưới mái nhà, là con thú bồn chồn lớp học, là cái cây rễ cắm sâu và bật xa ngược hư không, là kẻ lạ mặt bước vào khu vườn thơ ấu và “trộm nghe câu chuyện của những người xa lạ không ngừng tự nói với chính mình”, một kẻ mở lòng về phía các tiếng khác trong khi sống trong tiếng Việt, một cư dân trái đất trong thế giới phản không tưởng. Tôi hàm ơn những lạc lõng, vấp váp, thương tổn, nỗi bất an bởi không khít vừa và nỗi khó khăn của việc học cách chung sống. Tôi hàm ơn đồng vắng, góc vườn ấu thơ, những con đường đến trường cố tình đi lạc, những chỗ ngồi lẻ trong thư viện. Tôi hàm ơn những bầu bạn trò chuyện cùng tôi, những con kiến, những con sâu, những lá cỏ, những người trong sách, những cuốn nhật ký, những kẻ lạ, những kẻ tôi an toàn bộc bạch mình trong những trò chuyện riêng và rộng. Tôi hàm ơn những xô dạt của từ ngữ đã cùng tôi học cách nhìn ngắm và tổ chức lại những suy tư lụn vụn của mình.

Tôi là một ham muốn hóa lỏng, để đổi hình và thẩm thấu.

Tôi là một ham muốn hóa lỏng, để vẫn có thể làm một mạch chảy trong đất, mà không khô kiệt.

Tôi là một ham muốn hóa lỏng, trong những tiếng rì rầm bất tận của các tiếng, để bay hơi nuôi dưỡng những rễ cây bật, trong khi không ngừng trò chuyện với đất.

utterances

(The Vietnamese version of this essay first appeared on Tia Sáng magazine (2017) and was re-printed in Măng Ta (Fall 2020). Its English translation was first published in the anthology of writings from the Asia-Pacific region, The Near and the Far, by SCRIBE press, Melbourne and London, 2019)

Utterance of mine, the Việt wellspring

Writing, when I was three or five, as I still re-imagine it: holding a chalk piece, a twig, crawling on the ground, the house floor, wandering aimlessly by the door, by Mother’s cabinet, scribbling the first marks, copying folk rhymes, drawing the names of the familiar and the strange. I reveled in that game of communication, relished in the fledgling means of linking a prematurely literate child with laboring adults whose only remaining meager pleasure was to watch children grow. But as my child-self grew, writing was no longer to reveal, to open up, to talk to, but the opposite: to conceal, to wrap up, to keep silent. I, with paper, ink, and juvenile imagination, made the excuse of

‘busy writing’, wishing to encase the lonesomeness, neglecting Mother’s utterance|call, avoiding confrontation, hiding from fears of exposure, and dreaming of worlds I had not visited. Fascinated and terrified, I sensed that words were listening, conversing, playing with me, me vaguely seeing myself bend down to look at the shadow in the wellspring, a dense shadow the color of dark water imprinted by the sky, my curious quivering before the wellspring depth of drifting ancient tales, tottering along the circle of curses down the deep.

The patient silence of the abyss urged me to open myself.

The paradox of writing has haunted me since: the one who thought herself hidden is uncovered in the scattered ashes of words on discarded notes, pieces of scrap paper brewing dust under the cabinet and drawer. A hiding place on display, words unveiling themselves.

I cannot help being/getting-to-be read, being/getting-to-be discovered, once I have written, and I have, by chance, let slip and, further, tempted strangers into that hiding place.

No way back, I must overcome the fear of being seen and touched by others. I have been better about calming my Midas ears, ears open to the murmur of trees, fields, others. And though ceaselessly reserved, at times frightened to the point of firmly folding back in, I seem to have been less distant and strange with other humans, or less distant and strange with myself, and I want to love that strange distance. I have stopped resisting, except for the resistance to stop, as the struggle to pry open the heart is a perennial struggle to heal and be present, a struggle to not vanish too soon.

I dwell in Việt utterances as if nestling under a blanket, a shield, a skin, or maybe, somewhen, a death cloth, a coffin lid—or have I always resided inside Việt utterances like the child’s shadow hiding in the wellspring?

Poetic utterances, a breed of utterance that activates my most shrouded part, become the ground where I plant, play, stay awake, asleep, intimate, and immense. Where does poetry come from and how do I know? From under the skin, words protrude in bouts of hunger for communication and loneliness, hunger for closeness and distance,

hunger for presence and absence, hunger for a bond that fills me with other beings. Daily poetic desires are laborious desires: a couple of moments of pure ecstasy and sensual outburst in exchange for a stoic patience with utterance|tongue lessons. I am sketching a poetic way of life rather than struggling to merely produce poems: the resilient cohabitation with words, the caretaking of word-beings that squirm within claustrophobic bodies, demanding to grow and live their life. I look after such poetic utterances: a breed of utterance where myriad syllables and letters are present and squiggling together.

At times, with more outgoing confidence, I have thought I could use Việt utterances to convey myself, to tame words with ideas. Now, I hesitantly learn how to not use Việt utterances. I learn to listen to words breathing and sometimes softly touch these animate beings. I learn that lessons are always first about hurt and the hazardous capacity of words, where I, the one who learns to speak, to write, am ever fledgling and silent with scars.

Utterance of translation, an open vault

The wellspring opens heavenly vaults. A depth opens another breadth.

I bear gratitude for the translators who have gifted my pages with an alternative life, an experiment on the previous life, a parallel existence. The translation invites me on a voyage, a chance to escape the desiccating dilemma of staying too long in one place, straggling too long in a tunnel utterance, looking too long into the wellspring, the way I have lived too long in Việt utterances. I also think more of those writers who take shelter in translation as their only hope for survival and rebirth, the ones who are denied, amputated, or restricted from their readership and liveability in their home utterance|tongue, due to the chances of fate or, in many cases, the terrorizing scissor blades of cultural censorship systems. I think of the equal presence of all spoken and written utterances, the struggle to emit a sound by utterances slipping into oblivion or neglect, or the tender mystery of tenors and syllables that humans rarely, if at all, have the fortune to comprehend. I think of the space–time shuffle in the act of translation: the moving pieces of life from one locale to another, from one time frame to another, these space-traveling existences.

Certainly, a translation, like an original, could either be welcomed or rejected in a new territory. Skeptical readers still suspect if certain utterances of poetry can be translated, or readers might doubt if poetry can be read widely outside of its original utterance|tongue. The different utterances of translation themselves carry their own complications: a poem translated into one particular utterance|tongue reads better than in another. Which Việt poetics could gracefully rhyme in multiple utterances of translation? How differently do we feel when reading Tang poetry in transliteration, Vietnamese translation, and English translation? The hard-to-replace and the untranslatable of a tongue are often thoroughly enclosed, and in many cases they might well be its best treasures. And certainly there are utterances, or utterance users, that adamantly resist the intrusion of outside utterances, a violent resistance or feeble self-defense.

But I would like to think of and expect the points of collision and encounter, as in love, where utterances|voices might let go of resistance and take in the strangers, the outsiders. Poetry, no matter how attached it is to the original text, the original utterance|tongue, I trust, is interminably generous to possibilities of translation, possibilities that traverse tongues and territorial borders.

In fact, our bodies are constantly living and breathing utterances of translation everywhere. And it is perhaps essential to unravel plural ways of seeing and being seen within and across utterances.

Utterance of earth, the uprooted

Earth, a metaphorical mother, worries for trees that do not grow roots, uprooted trees, dried roots and bare trunks incompatible with the land. Uprooted, in Vietnamese, is hardly separated from a sense of loss and betrayal. We say mất gốc, ‘to have lost the root’, grunting a vicious condemnation: a ruling of banishment, a ruling that easily leads to brutal enmity and rejection.

Turning around: an Orphean plight that commands the price of infernal darkness. There are those who, whether departing or staying, whether grounded here or nomadic elsewhere, live their whole life with this tension: the impossibility of not turning around and the impossibility of turning around.

I don’t consider myself fortunate enough to have escaped questions of earth. Like my fellow Vietnamese writers, I want to both cease from caring and continue to hold on tight to Vietnamese, a tongue, a sound, a voice, an utterance, a word, a land, a water, a condition, a fate, a wound, a ghost, a loss. Like writers everywhere, I would like to be a part of the now, the everywhere, the here as always the elsewhere. I want to see Việt utterances traveling in concert with other utterances. I am a Vietnamese self-estranged in her homeland, a Vietnamese here and forever washed up on distant shores. I remain skeptical of the absoluteness of blood relations and concepts of identity. I am a stranger familiar with other strangers. The gradual recognition of the boundaries and characteristics of Việtness here or there comes with the gradual recognition of the elimination and loss of Việtness in me. A chronic case of agitation: yearning for a childhood realm, settling on a choice to uproot, to drift, to leave behind homes, promises, to not yet turn around, a conscious inevitability, or a fickle force of fate, even as I am still here in the homeland.

I am a lost child amid gatherings under warm roofs, an agitated animal in the classroom, a tree deep-rooted and pulled to the vacuum, a stranger entering the childhood garden and ‘eavesdropping on the old stories of strangers who soliloquize without end’, one who unfurls before other utterances while inhabiting Việt utterances, an earthly resident in a dystopia. I bear gratitude for losses, stumbles, injuries, apprehensions about being unfit, difficulties in learning to live together. I bear gratitude for empty fields, childhood garden corners, a purposefully lost journey to school, single seats in the library. I bear gratitude for the interlocutor-friends, the ants, the worms, the leaves, the humans within books, the diaries, the strangers, those with whom I safely unwrap myself in conversations intimate and immense. I bear gratitude for drifting words that have accompanied me in learning how to behold and re-organize my own fragmented thoughts.

I am a deliquescing desire, to shape-shift and osmose.

I am a deliquescing desire, to flow on as a current underground, not yet depleting.

I am a deliquescing desire, among the infinite murmurs of utterances, to evaporate and permeate the uprooted, while ceaselessly conversing with earth.

24.12.2016

| Translator’s note: The word tiếng, translated as ‘utterance’ in this essay, is poly-meaningful in Vietnamese. It appears in a range of expressions: tiếng Việt (the Vietnamese language), tiếng mẹ (mother’s call), tiếng thơ (poetic sounds), | and so on. Nhã Thuyên and I, after deliberating over a teapot on a Sunday afternoon, decided to approximate the omnipresence of tiếng in the original essay by settling on the vertical bar: tiếng as ‘utterance’ on one side of the glyph, and as a more contextual translation on the other, no space in between. I think of these pairs as newborn cases of conjoined twins, occurrences in which one appearance drags along another, adhesions in the deep tissues of each tongue, vexing linkages that are infinitely perplexing, perhaps life-threatening if clinically separated. |