لكن المنـفى ينبت مرة أخرى كالحشائـش البرية تحت ظلال الزيتـون | Exile sprouts anew, like untamed grass beneath the shade of olive trees

April 24, 2024

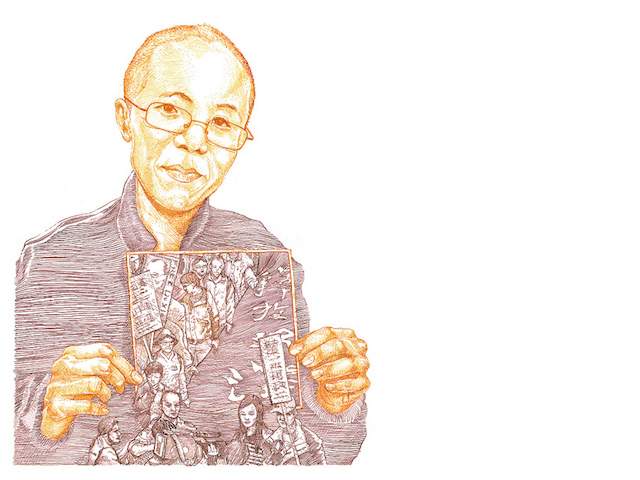

This essay and its translation are part of Transpacific Literary Project’s monthly column, with art by Mit Jai Inn.

المنفى المتدرج

لم تـنـتهِ الطـريق لأقـول، مجازاً، إن الرحـلة ابتـدأت. فقد تـُفضي بي نهاية الطـريق إلى بداية طـريق آخـر. وهكـذا تبقى ثنائية الخـروج والدخـول مفـتـوحة على المجهـول.

كنـتُ في السادسـة من عمري حين خرجـت إلى ما لا أعـرف، حين انتصر جيش حديث على طفـولة لم يكن يأتيها من جهة الغـرب إلا رائحـة البحر المالحـة، وغـروب شمس الذهـب على حقـول القمح والذرة. لم تتحول السيـوف إلى محاريث إلا في وصايا الأنبياء. وانكسرت محاريثـنا في الدفاع عن طمأنينة العـلاقة الأبدية بين ريفـيِّـين طـيِّـبـين وأرض لم يعـرفوا غـيرها ولم يولـدوا خارجها، أمام حرب الغـرباء المدججين بطائـرات ودبابات وفـَّرَت لرواية حنينهم البعـيد إلى ”أرض الميعاد“ شرعـية القـوة. كان الكتاب يتغـذى من القـوة، وكانت القـوة في حاجة إلى كتاب.

منذ البداية، صاحـَبَ الصراع على الأرض صـراعاً على الماضي والرموز. ومنذ البداية، كانت صورة داود هي التي ترتدي دروع جوليات، وكانت صورة جوليات هي التي تحمل حجر داود.

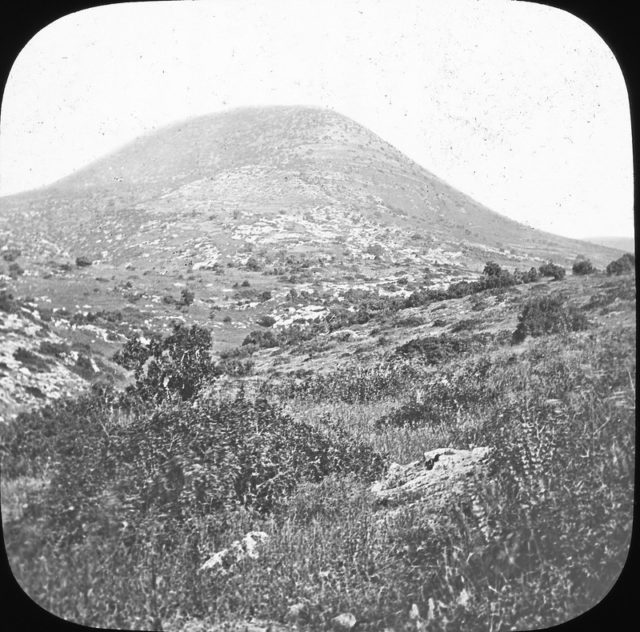

ولكنَّ ابن السادسة لم يكن في حـاجة إلى من يـُؤرِّخ له، ليعـرف طريق المصائـر الغامضة التي يفتحها هذا الليـل الواسـع الممتـد من قرية على أحـد تلال الجليل، إلى شـمال يضيئـه قمـر بدوي معلق فـوق الجبال: كان شعـب بأسـره يـُقـتـَلع من خبـزه السـاخن، ومـن حاضره الطـازج ليُـزجَّ به في ماض قادم. هـناك… في جنـوب لبـنان، نـُصِبت خيام سـريعة العطـب لنا. ومنـذ الآن، سـتتغيـر أسـماؤنا. منذ الآن سنصير شيئـاً واحـداً، بلا فروق. منذ الآن، سـنـُدمَـغ بخـتم جمـركي واحـد: لاجـئون.

-ما اللاجـئ يا أبي؟

– لا شيء، لا شيء، لن تفهـم.

– ما اللاجئ يا جـدي، أريد أن أفهـم.

-أن لا تكـون طفـلاً منذ الآن!

لم أعـد طفلاً، منـذ قليل. منـذ صرت أميـز بين الواقـع والخـيال، بين ما أنا فـيه الآن وما كان قبـل ساعات. فهـل ينكسـر الزمـان كالزجاج؟ لم أعـد طفـلاً منذ أدركـت أن مخيمات لبنان هي الواقـع وأن فلسـطين هي الخـيال. لم أعـد طفـلاً منـذ مسَّـني ناي الحـنين. فكلما كبـُر القمـر على أغصان الشـجر حضرت فيَّ رسـائـل مبهـمة إلى: دار مربعـة الشـكل، تتـوسـطها توتـة عالية، وحصان متـوتـر، وبرج حـمام، وبئـر. على سـياجها قفـير نحـل يجـرِّحـني مـذاق عسـله، وطـريقان معشـوشـبان إلى مدرسـة وكنيسـة، واسـترسال يفيـض عن لغـتي…

-هل سـيطول هـذا الأمـر يا جـدي؟

-إنها رحـلة قصـيرة. وعـما قليل نعـود.

لم أعـرف كلمة ”المنـفى“ إلا عنـدما ازدادت مفـرداتي. كانت كلمة ”العـودة“ هي خبـزنا اللغـوي الجـاف. العـودة إلى المكـان، العـودة إلى الزمان، العـودة من المؤقـت إلى الدائم، العـودة من الحاضر إلى الماضي والغـد معـاًً، العـودة من الشـاذ إلى الطبيعي، العـودة من علـب الصفيح إلى بيـت من حجـر. وهكـذا صارت فلسـطين هي عكـس ما عـداها. وصارت هي الفـردوس المفـقـود إلى حـين …

حـين تسـللنا، عبـر الحـدود، لم نجـد شـيئـاً من آثارنا وعالمـنا السـابق. كانت الجـرّافـات الإسـرائيلية قد أعادت تشكيل المكان، بما يوحي بأن وجودنا كان جـزءاً من آثار رومانـية، لا يـُسـمح لنا بزيارتـها. وهكـذا لم يجد العائـد الصغـير إلى ”الفـردوس المفقـود“ غير ما يشيـر إلى أدوات الغـياب الصـلبة، والطـريق المفـتـوحة إلى باب الجحيم.

لم أكـن في حاجة إلى من يؤرّخني، أنا الحاضر الغائـب. ولكـن المخـرجة السـينمائية سـيمون بيطـون سـتـذهـب بعد خمسين عامـاً إلى مسقـط رأسي لتصوير بئـري الأولى وماء لغـتي الأول، وستصطـدم بمقـاومةٍ من سـكان المكان الجـدد، وتسجـل هـذا الحـوار مع المسـؤول عن المستـوطنة الإسـرائيلية:

-لقد ولـد الشاعـر هـنا.

-وأنا أيضاً. حين وصل أبي إلى هـنا لم يـَلـقَ سـوى الأطـلال. أعطـونا خياماً ثم أكـواخاً. أنـفـقـت عشـرين عاماً في بناء بيـت لي، وتريدينني أن أعطـيه إياه؟

– ما أريده هـو أن أصـور هـذه الأطـلال، أطـلال ما تبـقـى من بيـته. إنه في عمـر والـدك، ألا تخجل؟

– لا تكـوني سـاذجة، إنهم يريـدون حق العـودة.

– أتخاف من أن يحصلوا علـيه؟

– نعـم.

– وأن يطـردوك كما طردناهـم؟

– أنا لم أطـرد أحـداً. أنـزلـونا من الشاحـنات وقالـوا لنا: ههـنا تدبروا أمركم. لكـن مَن هـو درويـش هـذا؟

-إنه يكتـب عن هذا المكان، عن شجرات الصبار هـذه. عن هـذه الأشـجار، وعن البئـر.

-أية بئـر؟ هـناك ثماني آبار. كم كان عمـره؟

– سـت سـنـوات.

-وعن الكنيسـة؟ هل يكتب عن الكنيسـة؟

كانت هـناك كنيسـة لكنها دُمِّـرت. أبقـوا على المدرسـة من أجـل البقـرات الحلـوبات والعجـول.

– حـولتـم المدرسـة إلى إسـطـبل؟

– لم لا؟

-صحيح، لم لا بالنهـاية؟ هم كان عندهـم حصان؟ هل ما زال هـناك بعض أشجار الفاكـهة؟

– طبعاً، حين كـنا لا نزال أولاداً اعتـشـنا على ثمـارها: تيـن وتـوت وكـل ما خلق الله. إنها كل طفـولتي تلك الأشـجار.

-وطفـولتـه أيضاً.

لم تكن صحراءٌ إذاً، ولا خالـية من السـكان. يولـد طفـل في سـرير طفـل آخـر. يَشـرب حليـبه. يأكـل توتـه وتيـنه، ويواصل عـمره، بدلاً منه، خائفـاً من عـودته، وخالـياً أيضا من الإحسـاس بالإثـم، لأن الجـريـمة من صنع أيـدٍ أخـرى ومن صناعة القـدر. فهـل يتسـع المكان الواحـد لحياة مشـتركة؟ وهـل يقـوى حـُلمان على الحـركة الحـرة تحـت سـماء واحـدة، أم أن على الطفـل الأول أن يكـبر بعـيداً وحيـداً بلا وطـن وبلا منـفى، لا هـو هـنا ولا هـو هـناك!

سيموت جـدي كمـداً، وهـو يطل على حياته التي يعيشها الآخـرون، وعـلى أرضه التي سـقاها بدمـوع جلده ليـورثها لأبنائه. سـتقـتـله رائحة الجغـرافيا المنكسـرة على إطلال الزمان. لأن حق العـودة من رصيـف الشارع إلى الرصيـف الآخر، لا يتحقـق إلا مع مرور ألـفي عام على غـيابٍ يكـفي لتطابـق الخـرافة مع الحـداثة.

أما أنا، فسأبحـث عن ”أخـُوّة الشعـوب“، في حـوار لا ينتهي، عبـر باب الزنـزانة، مع سـجان لا يكـُف عن الإيمان باني غائـب

– من تحـرس إذاً؟

– نفسي القـلقـة.

-مم أنـت قـلق يا سـيدي؟

– من شـبح يطاردني. كلما انتصـرت علـيه ازداد ظهـورًا.

– ربما لأن الشبح هو أثـر الضحـية على الأرض؟

لا ضحيـة سـواي. أنا الضحـية.

– ولكنـك القـوي، القـادر، السـجان، فلماذا تـنازع الضحـية على مكانـتـها؟

– لأبـرر أفعـالي، لأكـون على حـق دائماً، لأصـل إلى مرتـبة القـداسـة، ولأنجـو من داء النـدم.

– ولماذا تحتجـزني هـنا. هـل تظنني شـبحاً؟

ليس تماما. بيـد أنـك تحفـظ اسـم الشـبح.

لعل الشـعـر هو حافـظ الاسـم بجنـوحه الدائم إلى تسـمية العـناصر والأشـياء الأولى في لعـبة لا تبـدو بريـئة لمن يـُسـِّيج وجوده بالاستحـواذ المطلق على المكان وذاكرتـه، على التاريخي والغـيبي معاً. لعـل الشعـر لا يكـذب ولا يقـول الحقيقـة أيضاً شأنه شأن الحلم. ولكن تجربة الاعتـقال المتكررة أضاءت لي الـوعي بجمالـية الشعـر وجـدواه وفاعـليته. لا، لم يكـن الشعـر لعـبة بريئة ما دام يدل على كائن كان ينـبغي له ألا يكـون.

لكن المنـفى ينبت مرة أخرى كالحشائـش البرية تحت ظلال الزيتـون. وعلى الطائر وحـده أن يوفـر للسماء البعـيدة نقـطة العـلاقة بأرض أُخرجـت من خصالها السـماوية.

لا تتمتـع جغـرافـيات كـثيرة بوفـرة التعـدد الجمالي الذي تمتـاز به أرضنا العاجـزة عن إجـراء الانفـصال الضروري عليها بين الواقـع والأسطـورة. كل حجر هـنا يروي، وكـل شـجرة تحكي عن الصراع بين المكان والزمان. كـلما ازدادت وطـأة الجـمال ازداد إحساسي بخـفـة الغـريب: أنا حاضر وغائـب وسجـين. نصف مُـواطـن ولاجئ كامـل الحـرمان. أذرع شـوارع حيـفا، عـلى سـفح الكرمـل المـوزع بين البحـر والبـر، وبي عطـش إلى توسـيع رقـعة الأرض بحـرية لا أجـدها إلا في قصـيدة تأخـذني إلى الزنـزانـة. منـذ عشـر سـنين لا يـُؤذن لي بالخـروج من حيـفا. ومنـذ اتسـعـت دائـرة الاحـتلال الإسـرائيلي عـام 67 ضاقـت مسـاحة إقامتي: لا يـُؤذن لي بمغـادرة غرفـتي منـذ غـروب الشـمس حـتى شـروقها. وعليَّ أيضاً أن أثبت وجـودي في مركـز الشـرطة في الساعـة الرابعـة من بعـد ظهـر كل يـوم. أما ليـلي الخاص، ليـلي الشخـصي فلم يعـد لي: من حـق رجال الأمـن أن يطرقـوا بابي في أية سـاعة شـاؤوا، للتأكـد من أنني موجـود!

لم أكن موجـوداً. كنـت أرغـَم على العـودة إلى المنـفى التـدريجي تدريجـياً، منـذ اختـلطت حـدود الوطـن والمنـفى في ضباب المعـنى. وكنـت أحـدس بأن في وسـع اللغـة أن ترمـم ما انكسـر، وأن توحـد ما تشـتت. ولعـل ”هنا“ يَ الشعـرية المتحـولة من أفـق إلى قـيد، كانـت في حاجـة إلى توسـيع منطق البعـيد.

لكن المسـافة بين المنـفى الداخـلي والخـارجي لم تكـن مرئـية تماماً. كانـت مجازية ما دامـت هذه البـلاد، معـنىً، أصغـر من مكانها. وفي المنـفى الخـارجي أدركـت كم أنا قـريـبٌ من بعـيدٍ معاكـس، كم أن هـناك كانـت هنا. لم يعـد أي شيء شخـصياً من فـرط ما يحـيل إلى العام. ولم يعـد أي شيء عامّـاً من فـرط ما يمـس الشخـصي. سـتطـول الرحـلة على أكـثر من طريق غالـباً ما يُحمَـل على الكتـفـين. سـتـتـأزم هـوية محـرمة تسـتعـصي على التـلخيص بـ: هجـرة وعـودة. ولا نعـرف أيـنا هو المهاجـر: نحن، أم الوطن. والوطـن فـينا بتفاصيل مشـهـده الطبيعي، تتطـور صـورتـه بمفهـوم نقـيضه. وسيفـسَّر كـل شيء بضده. سـينمو كثيـر من النرجس الجـريح على أرض الهـامـش المؤقـتة. سـتحل اللغـة محل الواقـع، وتبحـث القـصيدة عن أسـطورتها في مُجـمل التجـربة الإنسـانية، وسيصـير المنـفى أدباً، أو جـزءاً من أدب الضياع الإنسـاني، لا لتـبرد نار التـراجيـديا الخاصة، بل لتـَدخـل في تاريخها البشـري العام. لكن الإسـرائيليين سـيطاردون هـذه المكانـة. سـيقـولون إنهم هم المنـفـيون. هم المنـفـيون الذيـن عادوا، وأن الفلسـطينيين ليسـوا منـفـيين، بعـدما عادوا إلى العـيـش في مجالهـم العـربي! سـتجرد الضحية مـرة أخرى من اسـمهـا. فكما أن مـن حق الضحية الخاصة أن تخـلق ضحيـتها، كـذلك من حق المنـفِيِّ الخاص أن يخـلق منـفـيِّه!

سـيتاح لي، بعد ما يـزيد عـن ربـع قـرن، أن أرى جـزءاً من بلادي، غـزة التي لم أرها من قـبل إلا في قصائد شاعـرها الراحـل معـين بسيسـو الذي جعـلها جنـته الخاصة. الطـريق إليها عـبر صحراء سـيناء موحـش يسـامره نبـتٌ صحراوي هـنا وهناك، نخيل حار ودبابة تذكـارية، وبحـر على الشـمال. أما مشاعـري فقـد كانـت مُرتـبة بعقـلانية باردة حينـاً، ونهـباً لحيـرة مـَن يعـرف الفـارق بين الطـريق والهـدف حيناً آخـر. تكاثر النخـيل فجـأة في العـريـش. ها أنـذا أقـتـرب من المجهـول الذي تمنيـت لو يطـول. ولكن سلطـة الوعـي على القـلب تتراخى تدريجـياً: هيا بنا قـبل أن يهـبط المساء. انتظر، قال لي صاحـبي وزيـر الثـقافـة، فالوطن في متناول اليـد. والوطـن هو ما تحـس به الآن. هـو هـذا التـوجـس وهـذا الاضطراب. قلت: لعلـه هـو هـذا المسـاء الذي يتأهـب فـيه الحلم ليصبح أكثـر واقعـية.

لا أحلم الآن بشيء. من هـنا تبـدأ فلسـطين الجـديدة: من هـذا الحاجز الإسـرائيلي. سـيارة جيب عسكرية، علم، وجندي يسـأل المرافـق بعـربية رخـوة: شـو معك؟ فيقـول له: معي وزيـر، وشاعـر. أتحاشى النظر إلى كاميرات المصورين الباحثة عن فـرح العـائدين إلى الجـنة. وتـلسـعني أضواء المسـتوطنات وحواجز الجيـش الإسـرائيلي على جانبي الطريق. ولعـل أول ما يفاجئني هو انكسار القـوام الجغـرافي وتشـوه الخارطـة. ولكـن للمفاجأة جوابها الجاهـز: هذه هي البداية. غـزة وأريحا أولاً، فنحن في أول الطريق، في أول الأمـل. لم أتمكن من الوصول إلى أريحا. فكيف أصل إلى الجلـيل، وطـني الشخصي؟ كان ذلك مشـروطاً بشـروط قال لي إمـيل حـبيبي إنه يخجل من نـقـلها. لكنه لم يعـرف أنه سـيرحل بعـد عامـين، وأن جنازته ستـوفـر لي فرصـة حزيـنة لأفـرح بعـودة قصيرة إلى الجلـيل، إذ حصلت على تصريح لمـدة ثلاثـة أيام للمشاركـة في تأبيـن إمـيل حبـيبي ولزيارة بيـت أمي. وهـناك احترقـت بلهـفـة العـودة، فمن هـنا خرجـت والى هـنا أعـود. ورأيـت كيـف يسـتطـيع المـرء أن يولـد من جـديد: كان المكان قصـيدتي.

لم ينـقـصني شيء لأحقـق موتي المُـشـتهى في ذروة هـذه الولادة. بيـد آني، وأنا أُحـرَم من اكـتمال الدائـرة، كنـت أدرك أن انسـلاخ الأسطـورة عن الواقـع ما زال في حـاجة إلى مزيـد من الماضي، وأن تحـرر الواقـع من الأسـطـورة ما زال في حـاجة إلى مزيـد من المسـتقـبل. وأما الحاضر، فلم يكن أكثـر من زيارة يعـود الزائـر بعـدها إلى توازنه الصعـب بين منـفى لا بد منه وبين وطـن لا بد منه. فلا يُعـرّف هذا بعكـس ذاك، ولا ذاك بنقيـض هـذا. فـفي كل وطـن منـفى، وفي كل منـفى بيـت من شـعـر.. ولم أعـد بعـد. لم تنـتـه الطـريق لأقـول مجـازاً إن الـرحـلة ابتـدأت.

من ملفات مجلة الكرمل – العدد 60 صيف 1999

The Gradual Exile

The road has not ended for me to claim, metaphorically, that the journey has even begun. For the end of one path may lead to the start of another, and the duality of exiting and entering remains an enigma.

I was six years old when I ventured into the unknown. A modern army triumphed over a childhood that knew, from the west, only the salty scent of the sea and the golden sunsets over fields of wheat and corn. Swords did not turn into plowshares except in prophetic teachings. Our plows broke in defense of the tranquility shared by two kindhearted villagers and their beloved land, a land they knew no other than, and inside which they were born. This tranquility faced a war waged by foreigners who, armed with airplanes and tanks, legitimized their distant claim to a “Promised Land” through brute force. The scripture fed on power, and power needed a scripture.

From the onset, the struggle to conquer the land moved hand in hand with the one to conquer the past and its symbols. Early on, David donned Goliath’s armor, and Goliath wielded David’s stone.

But for the child of six, no chronicler was needed to navigate the mysterious paths destiny had lain beneath the vast sky, a journey stretching from a village perched upon the Galilean hills, bathed in the silver glow of a bedouin moon high above the mountains. Here, an entire nation was torn from its warm bread, from a present so vividly alive, and cast into a past yet to come. In the south of Lebanon, decaying tents were hastily erected to house us. Henceforth, our names will change. Henceforth, we would meld into one shapeless mass. Henceforth, we would all bear the same mark, a shared customs stamp: Refugees.

– What is a refugee, Father?

– Nothing, nothing, you wouldn’t understand.

– What is a refugee, Grandfather? I want to understand.

– To not be a child anymore!

Recently, I became no longer a child. The veil between the tangible and the imagined, between the world I inhabited then and the one I had hours before, began to lift. Does time fracture like glass? I became no longer a child when I realized that the camps in Lebanon were reality and Palestine was fantasy. I became no longer a child when the melodies of the flute of longing caressed me. Each time the moonlight spilled over the tree branches, it summoned memories: a home, shaped like a square, a towering mulberry rising in its center, a horse charged with tension, a pigeon tower, and a well. Around the house’s fence, a beehive with nectar that stung, while twin verdant trails beckoned towards a school and a church, and a language so vast that it sloshed over the boundaries of my words.

– Will this take long, Grandfather?

– It’s a short journey. We’ll be back soon.

I only learned the word “exile” when my lexicon grew. “Return” had been our dry linguistic bread. A return to a place, to a time—from the temporary to the permanent, from a present to a past and a future intertwined, from dissonance to harmony, from tin cans to a stone house. Thus, Palestine morphed into the contrast of our very life, a paradise lost—momentarily.

When we finally snuck across the border, the land greeted us with not a trace of our past life. The Israeli bulldozers had sculpted the landscape anew, our existence an inaccessible ancient Roman ruin. The child returnee to “paradise lost” met nothing but unyielding artifacts of absence, and an open descent towards infernal gates.

I needed no historian to narrate my tale: I was both absent and omnipresent. Yet, fifty years on, filmmaker Simone Bitton would journey to my birthplace to capture my first well whose water nourished my language into being. She would brush against the resistance of those who had since claimed dominion over the land, and record this dialogue with the official in charge of the Israeli settlement:

– The poet was born here.

– So was I. When my father came here, he found only ruins. They gave us tents, then shacks. I spent twenty years building my house, and you want me to give it to him?

– What I want is to film these ruins, what remains of his house. He’s as old as your father, aren’t you ashamed?

– Don’t be naive, they want the right of return.

– Are you afraid they will get it?

– Yes.

– And that they will expel you as we expelled them?

– I didn’t expel anyone. They dropped us off from trucks and said: Here, manage. But who is this Darwish?

– He writes about this place, about these cacti, these trees, and the well.

– What well? There are eight wells. How old was he?

– Six years old.

– And the church? Does he write about the church?

There was a church, but it was destroyed. The school they kept for the milk cows and the calves.

– You turned the school into a stable?

– Why not?

– Right, why not, after all? Did they have a horse? Are there still some fruit trees?

– Of course. When we were still children, we lived on their fruits: figs, mulberries, and all that God created. Those trees are my entire childhood.

– And his childhood, too.

So, the land was neither barren nor forsaken. A child was born in another child’s bed, drank the other child’s milk, ate their figs and mulberries, and took over their life, haunted by the specter of their return, untouched by remorse, for the transgressions were the crimes of destiny.

Can a single space accommodate a shared life? Can two dreams meander under the same sky? Or is the first child fated to grow far away, wander in solitude, belonging neither to homeland nor exile, suspended between a here and a there?

My grandfather would die of grief—one born from the sight of strangers traversing the paths of his life, over the land he had nurtured with the weeping of his flesh to bequeath to his children. He would be murdered by the fragrance of a geography shattered upon the altar of time. For the right of return, even from merely one street corner to another, becomes attainable only after two thousand years of absence, a span long enough for myth to blend into the fabric of the present.

As for me, I will search for the so-called “fraternity of peoples” in an endless dialogue through the prison door, with a jailer who’s never acknowledged my existence.

– Whom, then, are you guarding?

– My own restless spirit.

– And what, pray tell, troubles you so deeply?

– A ghost that haunts me. Every time I defeat it, its presence only sharpens.

– Could it be that the ghost is the imprint of the victim buried within the earth?

– No victim exists here save for myself; I am the victim.

– Yet, you are the powerful, the authority, the custodian—why do you wrestle the victim to claim their victimhood?

– For vindication, to assert my righteousness, to ascend to sanctity, all the while fleeing from the disease of remorse.

– For what purpose do you confine me within these walls? Am I to you a ghost?

– Not quite. But you carry the ghost’s name in your heart.

Perhaps it is poetry that stands guardian over the name, ever drawn to put to language the primal elements and beings. It is an endeavor that appears far from benign to those who delineate their being with absolute claims over place and memory, the historical and the mystical. Perhaps poetry, like a dream, neither deceives nor tells the truth. Yet, my recurring experiences of incarceration have illuminated to me the splendor, purpose, and potency of verse. Indeed, poetry will never be perceived as an innocuous endeavor when it points to an entity that should have never existed in the first place.

Exile sprouts anew, like untamed grass beneath the shade of olive trees. The bird alone must weave back the distant heavens with a land stripped of its celestial grace.

Whereas the line between fable and reality blurs on its soil, our land basks in a wealth of aesthetic diversity unmatched by any geography. Each stone within it whispers tales, and every tree speaks of the perpetual tension between place and time. The heavier the beauty, the more it renders the stranger in me lighter: me, the present, the absent, and the incarcerated. Half a citizen, and a refugee fully stripped.

My footsteps echo through Haifa’s streets, tracing the Carmel’s ridge as it cleaves sea from soil, yearning for the land to grow through a freedom I find solely in a poem that lands me in a prison cell. Since the expansion of the Israeli occupation in 1967, my life has shrunk: confined to my room from dusk to dawn. Forced to record my presence at the police station every afternoon at four o’clock. The privacy of my night, once my own, no longer belonged to me. Security forces had the right to knock my door down at the hour of their choosing, ensuring my presence.

I was no longer present, forced back slowly into a gradual exile where the boundaries of home and diaspora seeped into one another in the mist of meaning. I sensed that language had the power to repair what was broken, to unite what was scattered. The poetic “here” I inhabited—once a vast horizon, now a chain—ached to stretch the meaning of distance.

The inner and outer exiles blend, fading into metaphor, for this land—rich in meaning—dwarfs its physical confines. In the external exile, my proximity to the distant became palpable; there melded into here. Nothing remained personal, for all slipped into the collective. And nothing remained collective, for all touched the personal.

The journey stretches along manifold paths borne upon weary shoulders. A forbidden identity will emerge, defying the binary of departure and return. We do not know any longer who the migrant is: us or the homeland. The homeland, juxtaposed with its natural details against its opposites, evolves within us. Everything will be interpreted by its contrast. Many injured narcissi bloom in the transient soil of the margins. Language supplants reality; poetry scours the breadth of human experience for its legend. Exile thus becomes literature, a segment of the narrative of human loss, not to soothe its inflamed tragedy, but to inscribe itself into the annals of its collective human memory.

The Israelis pursue even that status. They proclaim themselves the exiles who have found their way back, while asserting that the Palestinians are not exiles, for they have resettled within their Arab territories. Once again, the victim is stripped of their identity. Just as the exceptional victim holds the privilege to redefine their own victim, the exceptional exiled claims the right to redefine their own exiled.

A quarter of a century later, the gates would open before me for a glimpse of my homeland: Gaza, previously known to me only through the verses of the late poet Muin Bseiso, who enshrined it as his own Eden. The path through the Sinai desert to reach it was a solitary one, marked by the occasional desert flora, a palm hot to the touch, and a memorial tank, with the sea to the north. My emotions oscillated between a cold, rational detachment and the turmoil of a soul torn by its knowledge of the difference between journey and destination.

In Al-Arish, the palms began to proliferate. I approached the unknown I longed to linger within. As this proximity grew, the grip of awareness over my emotions subtly eased:

“We must hasten before night descends,” I urged.

“Hold,” said my companion, the Minister of Culture, “for the homeland lies just within reach. What stirs within you now—this mix of trepidation and unrest—that is the homeland calling.”

I said, “Perhaps it is in this evening that our dreams edge closer to reality.”

Dreams faded away. Here, at this Israeli checkpoint, unfolds a new Palestine. A military jeep, a flag, and a soldier interrogating our escort in flaccid Arabic, “What do you carry?” “A minister and a poet,” our escort replies. I avert my gaze from the lenses of photographers, hunting for the euphoria of those returning to an imagined paradise. The glare from the lights of settlements and Israeli army checkpoints stings me. The initial shock comes from the profound disfigurement of geography, the altering of the map’s very essence. Yet, this shock offers its own clarity: This is but the beginning. Gaza and Jericho first, for we are merely at the start, at the birthplace of hope.

I could not reach Jericho. How, then, could I return to the Galilee, my own homeland? This possibility was bound by conditions that Emile Habibi once confessed he would be ashamed to relay. Little did he know, death would claim him two years later, and his passing would provide me a bittersweet chance for a fleeting sojourn back to the Galilee. I secured a three-day permit to attend Emile Habibi’s memorial service and visit my mother’s home. There, the desire to stay engulfed me—for from this soil I had emerged, and to it, I am inevitably drawn back.

I witnessed then and there how one could be reborn: the place was my poem.

In my quest for a chosen demise at the pinnacle of rebirth, I found myself lacking nothing. Yet, as the circle remained incomplete, I came to understand that the chasm between myth and reality still thirsted for deeper histories, while the emancipation of reality from mythology yearned for more future. The present, however, amounted to nothing but a fleeting visit, after which one retreats to a delicate balance between the inevitable exile and the inescapable homeland. Neither is defined by the antithesis of the other. For within every homeland breathes an exile, and within every exile, a verse of poetry.

And I have not yet returned. The road has not ended for me to claim, metaphorically, that the journey has even begun.

From the archive of Al-Karmel Magazine, Issue 60 Summer 1999.