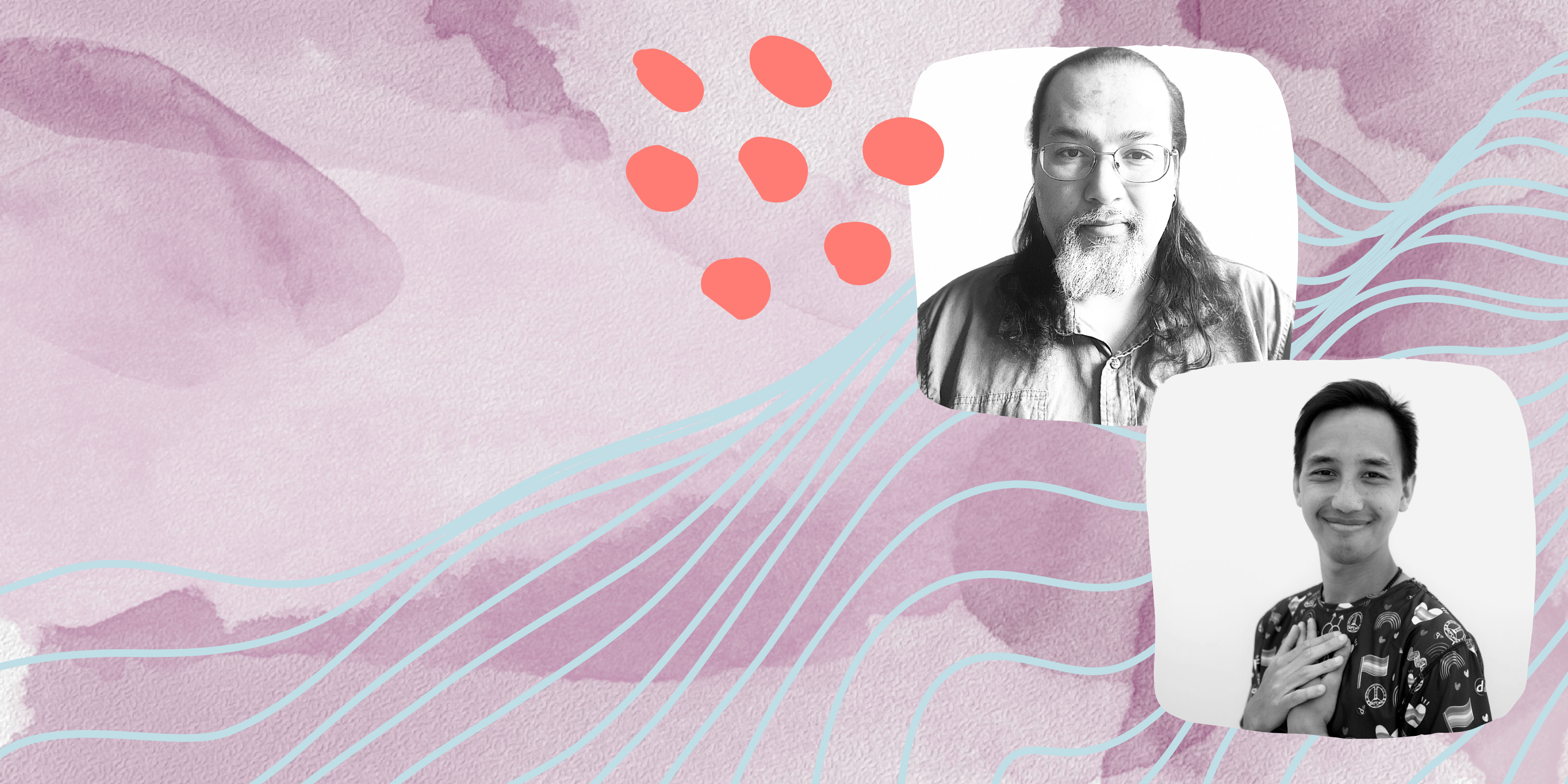

Deaf interpreters Xgamil Campos-Espinosa and Romduol Ngov in conversation

January 18, 2023

In September, AAWW hosted a conversation between Deaf interpreters Romduol Ngov and Xgamil Campos-Espinosa, moderated by AAWW events and workshops coordinator t. tran le. Ngov and Campos-Espinosa discuss their process for interpreting poems, the challenges and rewards of interpretation, advocacy within and for the Deaf community, and how with so much of their work, “it all leads back to language,” as Campos-Espinosa put it.

Gregorio Nieto and Jared Vincent of Pro Bono ASL interpreted for Ngov and Campos-Espinosa, respectively, and both Nieto and Vincent signed for le. The transcript of Nieto and Vincent’s interpretation of Ngov and Campos-Espinosa’s conversation is below the video and has been edited and condensed for clarity, with support from Rorri Burton from Pro Bono ASL.

t. tran le (ttl)

Hi, everyone. My name is t. tran le, and I am the programs and workshops coordinator at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop. A quick visual description of myself: I am a Southeast Asian diasporic person with very short black hair. I’m wearing big round glasses, red lipstick, a pink top, and my background is a pink curtain.

Today, we are so excited to feature an interview with wonderful Deaf ASL interpreters Xgamil Campos-Espinosa and Romduol Ngov about poetry, process of interpretation, and language. This conversation is in collaboration with our online magazine, The Margins; our friends at Pro Bono ASL; as well as the Poetry Coalition: a coalition of organizations dedicated to poetry programming. The Margins, our online journal, is an award-winning magazine of arts and ideas dedicated to charting the rise of the Asian American creative class through essays, interviews, and creative writing.

I’d like to give special thanks to our collaborators and friends at Pro Bono ASL and our interpreters for this event, Gregorio Nieto and Jared Vincent.

I’m speaking to you from the traditional and unceded land of the Canarsie and Munsee Lenape people, and as they are the stewards of this land, we thank them for allowing us the space on which we are based.

So without further ado I’d love to introduce our panelists for today—our Deaf ASL interpreters. Xgamil Campos-Espinosa is a Chicano hailing from Mexico, the motherland. Xgamil’s family uprooted from Mexico and moved to the United States, settling in Oakland, California, in pursuit of a better life. Xgamil was not certified as a Deaf interpreter for over twenty years, not realizing that being a Deaf interpreter for a living was possible.

Romduol Ngov is a Khmer, trans, genderfluid, and Deaf child of refugee parents. Romduol has been working as a Deaf interpreter for four years for a vast array of settings and programs.

We’re so lucky to have Xgamil and Romduol here with us today. Welcome. Xgamil will be voiced by Jared Vincent, and Romduol will be voiced by Gregorio Nieto.

Welcome, everyone. Thank you all for being here, and special thanks to our interpreters for interpreting. How are y’all doing today?

Xgamil Campos-Espinosa (XCE) 03:05

I’m doing good. I’m excited to be a part of this and to envision more exposure for Deaf interpreters. And I really do think it can benefit everyone to find more information about this.

Romduol Ngov (RN) 03:25

Same, I feel great about that. And I’m taking care of myself—got my water, so I’m ready to start this process! I’m really excited to be part of this discussion, because I think it is important, like you said, to expose Deaf interpreters. And there are so many different backgrounds—Indigenous and Black and people of color to show.

ttl 03:54

Thank you both for being here. I’m so happy to share space with you and to talk about poetry and language. I’m told there’s a special process for interpreting poems, and we all know how complicated and nuanced language can be in translation and interpretation. Poems are special, right? What are your processes for interpreting poems from the time you approach the poems for the first time?

RN 04:57

Before we get started, I want to describe myself and my background a little bit more. So, my visual background is gray. And I identify specifically as Cambodian. The word we use is Khmer. And that word has a lot of meaning to people with our language. It’s not a country, it’s people-based. We’re typically brown, have dark-brown hair. I’m wearing a shirt with teal sleeves and a darker-colored chest.

With interpreting and translation, I try to ask, or if I’m not informed I try to think “What is the topic? What is the meaning?” to help me envision what the purpose is for that work. When I’m given a poem, I try to look at the author, the writer: what kind of person they are, what their background is. I research as much as I can about who that person is and what the purpose was for their poem. That way, I can have a better vision when I go into my interpretation. We are trained to think about the meaning of a text and sign what that meaning is; we’re not signing word for word. We’re signing the meaning. That’s typically my process. And you?

XCE 06:37

So before I say anything, I am Xgamil. I have a green background, and I’m working in my office space. I’m wearing a black shirt with a long-sleeved button up. I have a gray beard, glasses, and long black hair, and I’m of Mexican descent.

I agree with Rom when they mention that it’s a lot of work. You have a rough draft, and then you have your middle draft, and then you have a final draft of what you think. With Deaf interpreters, we need to be able to observe what the right sign choice is for that context. Sometimes we can read and understand the English, but how do you translate it and get the message out of the language? Many people want to envision what interpreting means and think it’s interpreting word by word. But no, it’s interpreting the message. That is, at its core, what it is. So sometimes when we go ahead and we read the message and then we look at the sign, it looks different. But the point is that we’re getting at the meaning. As Deaf interpreters, it requires a lot of work and being involved in the process of figuring that out.

RN 08:15

To add to that, we have to make sure that the meaning is the same. And it’s a real challenge, because with poetry—and it’s the same with song lyrics—the biggest challenge is that they tend to use a lot of metaphors. They have a lot of meaning behind the words that they use. And so often when we use or translate metaphors, it’s not the same in ASL. And usually going from two languages—from English to ASL—we have to modify the metaphor. So we tend to not use the metaphors in our signs; we sign what’s actually being said. We expand on what’s being said, and we still get the point and the message across, but sometimes we drop a lot of that metaphoric language.

For example—it’s not a great example, but—in English, we say, “It’s raining cats and dogs.” And so when we sign that, we would not sign, “Cats and dogs are falling from the sky.” So we modify our sign to indicate what the meaning of that is. So when you see the sign and you have that vision of what’s happening, you can see that. We’re not signing that it’s raining cats and dogs—they’re not falling from the sky.

XCE 09:46

To add to what Rom just said: It’s not only the sign, but it’s our body language. It’s our facial expressions. And that’s what we have to show, because it’s not only the sign but also the visual cues. That is so important. We have to make alterations to convey seriousness or lightheartedness. We have to be able to convey that spectrum of emotions within our body language, our facial expressions, and also in our signs. So even the space of the signs, either it’s super big and we’re wide and out loud, or we condense it. And we’re very methodical with how we sign it.

ttl 10:40

Sounds like quite a creative process for you, too, because there’s so much work involved in processing context, identities, language, metaphors. That’s really interesting about metaphor. I was curious about that in poetry because there’s a lot of imagery and metaphoric language—thank you for explaining that.

What’s the most challenging part of interpreting poetry? And what’s the most rewarding?

XCE 11:40

The most challenging part is you have to be aware that Deaf interpreters are often not extremely skilled with English. So for example, when you’re reading any type of English text—let’s say if it’s coming from a book, or an essay, or anything along those lines—we have to take more time because we have to get the comprehension down of the words and then make alterations. So I would say the challenge, especially for Deaf interpreters—and I don’t mean that we’re bad, because there are some hearing people that struggle with English as well—I think just with English, the most complicated, tough thing is the linguistic aspect of it. When you go ahead and try to translate the English into ASL, there can be a lot of expansion and more complexities on top of that.

RN 12:48

Yes, and what would you say about the rewards?

XCE 12:54

The most rewarding thing is really the message in itself and its impact. Often, it’s a tough job to be an interpreter and just say, “Oh, we’re all good.” And the community says, “Oh, good job!” And that’s all. We show up and interpret, but where’s that feeling, that relationship? I really do like it when the community actually understands the message. And they’re very supportive of it, and they start to see the empowerment aspect of it. And they can actually get the message and have the whole meaning where previously they weren’t able to get it. And then there’s like that “ah” moment. That is the most rewarding part to me.

ttl 13:44

That’s amazing. Thank you.

RN 13:51

For me, it’s a singular experience. The most challenging thing, I think—we talked about English not being our first language, or having that experience of being an immigrant. In our community, we always have that discussion. Are we disabled, are we handicapped? There’s that conversation related to society and Deaf community about the barriers that we experience that we sometimes don’t have. We’re able-bodied, so we don’t have that disability, but we need access. Deaf people typically don’t have access to ASL. When they’re born, they don’t have that exposure until later in life most of the time. So thinking about language deprivation is a guiding thing. That affects our process and our ability to acquire language a little bit differently, and that’s where we struggle with the meaning related to English.

Another challenge with poetry translation is that you have to know the background, the context first. Maybe the person is from a different culture or has a different language. And with ASL, it’s not one sign fits all. We have different things behind our language itself. So, for example, there’s Black ASL, and we have different regional signs. There’s also diversity within our culture about language and how we express ourselves. So the most challenging part is being able to think about that. And then, do we have time to expand on a concept and poetry? Because sometimes we have to process so much of the meaning that’s there. And sometimes when a word uses sound play and that doesn’t work for us, we have to learn how to create that translation.

There’s so many layers. But the most rewarding part is that it’s inspiring when we get to see the Deaf community be inspired and have that connection to poetry. And we see it in their expressions. We see it when they are just taking in what we’re producing. And for us, it’s so exciting to see Deaf people inspired by seeing a Deaf person on stage. Because of that experience with language deprivation and so many of the barriers, we don’t have a lot of role models. So when Deaf people see a Deaf person on stage signing, it inspires them to realize, “Oh, I can do this,” or, “There are other options for me.” There’s so many other things, but that, for me, is the most rewarding.

XCE 17:01

Rom, you’re right. The challenging part is the cultural portion of it—conveying that culture is one thing, but also including the language. And that’s the biggest thing, the subcultures that we have and the different perspectives that are brought into it even in the translation process. So we also have to be aware that that cultural aspect is not lost in our translation of the poetry.

RN 17:35

Yes, I agree about the cultural adjustment that we have to put in because we’re channeling their culture, and we don’t want to lose that cultural component in the message. So we have to make sure that’s there. So often, we try to make sure that we put in an interpreter who is skilled or has lived experience of that culture that the content is from so they can better match that space. If someone isn’t familiar with that culture, often the meaning and the message is lost, or there’s misunderstandings, or there are so many different things that happen.

And that’s interesting, because a lot of interpreters are white, and the majority are white women. I think, in general, society’s expectations of women are that they get language acquisition, and they have that. And there’s different expectations and that kind of gender perspective on women. And so really, anyone can be involved in interpreting, but I think one of the problems that shows up.

Often there are a lot of barriers in interpreter training programs—we often don’t see Deaf interpreters, we don’t see Black or Indigenous or people of color. Often those are marginalized groups, and we don’t see a lot of the different backgrounds in the interpreting world and the interpreting field to provide these adequate interpretations.

ttl 19:20

Thank you so much for that context. You both brought up the intersection of being a Deaf ASL interpreter, audience, identity, and cultural competence. Is there a way that you approach your specific audience? How do you approach an audience and base your interpretation on that audience? Or is it just kind of a surprise every time?

XCE 20:25

Yeah, I think that Rom already touched on it. So when we get any type of assignment, we go ahead and we ask questions. We see what the framing is and its implicit and explicit messaging. Once we get that information, we’re able to conceptualize and match our audience. That’s where the cultural relevance is. We have to be able to match that culture with the specific audience. Often we’re able to ask those types of questions.

But there are also many vendors that ask us, “Well, why do you need that? What’s that for?” Then I have to explain it’s because that helps our preparation process and allows us to provide the utmost interpretation, the best interpretation we can, and give all of our effort into our work.

And that also helps because sometimes I might get an assignment and I can look at it and say, “I’m not the right representation for that.” But at the same time, I can also reach out to some people that I do know who would be a better fit for that assignment. And so that’s how I’m able to best advocate for our own interpreter community.

RN 22:00

Definitely agree with that. It’s so important that we ask questions and that we get more information so that we can provide that interpretation. And also, we have to make sure that we’re code-switching to match whatever environment. And again, what kind of language do we use? Because with ASL—I mentioned before that as Deaf people, we experience those barriers in communication and language acquisition. And hearing people have tended to create codes—it’s not a language, I want to be clear, it’s a code. One example is Signed Exact English. And that is, from a hearing perspective, the perspective that “Deaf people, ASL, and English—there’s not accurate translation, and we need to create a communication mode for Deaf people so that they can have a better understanding of English.” And that doesn’t always work. And it’s not a true language either. And so that’s just one mode of communication that is used.

That’s where we have a lot of different layers on the impacts of what our communication could look like, specifically with language and what our context is, what the background is, what the family perspective is. And often the medical perspective is included in that, because the medical perspective is that you are disabled, that you need to be fixed, and they want to throw out sign language. And they force us to go to speech therapy and take an oralist approach to experience our Deafness. And so that’s why we have to figure out with our audience, we’re trying to code-switch. Because I come as a person, and I’m trying to see what the preferred signed code modality is for that audience group so that I can best provide access.

And for platform and online—oh, that’s a whole other challenge—because often we don’t get to see the audience. We have to figure out how to make those modifications, sometimes in the middle. Are we going to use more ASL? Are we going to be closer to English? Are we using different codes in that space? So that’s, again, another layer. So it is a challenge trying to match our audience.

XCE 24:23

It’s not only those challenges that apply to Deaf interpreters. There are also many hearing family members who come from another country who are trying to learn maybe their second, third, or even fifth language. And so even with immigrants who move here—I notice interpreters have the same type of experience of listening to English and then trying to translate it into their own language and interpret the content, the context, and so on and so forth. There’s a very fascinating aspect in that we can take from other interpretive languages and apply it into the ASL context as well. There are a lot of parallels when it comes to those two things.

RN 25:20

I definitely agree. With Deaf interpreters and hearing interpreters, we have the ability to switch to match our audience and also to match our team so that there is effective communication between me and my hearing interpreter team, and we can work better together.

One layer that people don’t realize is that hearing people in general can learn our language, can learn about our culture, can pick up sign language and develop that, but they don’t realize—and research has proven—that it requires a minimum of seven years to be skilled in any language, to be comfortable using and picking up that language. So that includes, again, the cultural components and so many other things. And it’s impossible to learn about our lived experience as a Deaf person, and that’s where there’s a difference with Deaf interpretation and Deaf interpreters and our dynamics. What does it mean to be Deaf and to understand our culture? You can learn about a perspective, but you can’t have an in-depth understanding of that experience unless you’ve had that lived experience.

So with us as Deaf interpreters, we can connect to a Deaf audience or Deaf client in so many different ways through expression, through body language. Hearing people often don’t realize. As Deaf people, we can catch those really subtle adjustments in expression. And we tend to go back and forth with a hearing interpreter to create that clarification with each other. That’s where we’re able to pick up that experience, and other hearing interpreters can pick up our language and that understanding. But again, hearing interpreters will never have that understanding of a lived experience that we do. And that’s where we as Deaf interpreters can make those clarifications with our Deaf client, and have a better and more accurate interpretation.

ttl 28:00

This is such a rich conversation. You both have talked a lot about identity-specific nuances. When we’re dealing with languages—and you both touched on this a lot—we live in an imperialist country, right? We live in an imperialist system. And so there’s supremacy involved with language.

RN 28:42

That definitely applies to language. Absolutely.

ttl 28:47

What are y’all’s thoughts on this supremacy of language? And the different languages of sign as well?

XCE 29:12

Societal supremacy is definitely a thing. When it comes to Deaf interpreters, as Rom mentioned, there is a separation. So there’s a part of me that is an advocate. I’m always doing my best to fight for all of these things. And so I definitely do see there’s a linguistic problem, and it’s just how society creates it and how we all look at it.

And in this country, we’re late to have that, and also those legal protections, which has been happening for thousands of years. For example, spoken languages are well-established. And so when we look at English, it’s required from a linguistic aspect—and that is oppressive. There are a lot of communication missteps, a lot of communication breakdowns. That leads to so many barriers. Because even when we try to get medical needs or educational needs or services or a myriad of different things, it all leads back to language. That’s the lived experience. And that is the portion of our society that we live in.

Being a Deaf interpreter, but also being Deaf and Indigenous, there are just so many experiences of marginalization. There’s just so any things. And that all ties back to language. It’s really Deaf interpreters, they do work with hearing interpreters, often. And they always see hearing interpreters have a hard time communicating with their consumers. And so they say, “Oh, you sign that wrong,” or “Oh, you shouldn’t sign it like that,” and then give a reason as to why. But that’s already oppressive. In that action, that’s oppressive. In my job as an interpreter, I have to make sure that I interpret properly and that I’m in an interpreting role and not in the advocate role. So it’s just a delicate balance of where I’m at at being an interpreter and a Deaf person at the same time.

RN 31:43

Yes, I 100 percent agree. There’s so many layers to that. And talking about language supremacy—yes, it’s an issue. As Deaf people, society sees us as disabled, so we experience those barriers and that’s why we still are labeled disabled because of those barriers. And it’s not because of us—it’s because the world is not providing us access. So that’s why they give us that label.

So yes, there are a lot of problems with language supremacy. Because ASL isn’t just a sign language, but society doesn’t recognize it as a language and prefers English. Also, there is another layer, typically people who learn anything that is related to ASL, Deaf culture, and Deaf community from hearing people who’re not part of the Deaf community. Instead of learning ASL and Deaf culture from us, Deaf people who are part of the Deaf community. But we’re sometimes learning it from a hearing person; that’s where we’re getting that access. Not through an ASL teacher, not through the community. So many of us have that accessibility through hearing people, and based on their decisions and on their ethics. They’re deciding so many things for us. It’s not always great.

For example, when a trainer that I had made a comment, and I had to challenge that. I want to challenge your perspective on your own expectation of the work. But you never thought about asking me as the Deaf person what I thought about the message in our training program that happened. With all of these different modalities to make sure that that matched what the client needed, you never thought of that! You never thought to ask me. You never thought to ask for the Deaf perspective. We learned through a hearing lens and not a Deaf lens.

And so, we ask each other for feedback in the interpreting community as colleagues, but often they never ask the audience. They never ask the client: what was your expectation? Or how do you feel about the experience? And so we as Deaf people are intimidated about commenting and giving feedback to the interpreter, because we fear losing our access—if the interpreter becomes upset, if they have white fragility. People get upset and have that fragility. Sometimes a hearing savior complex can develop, where the hearing interpreter will say, “Oh, you should be grateful that I’m providing you access. You should be grateful that I’m providing this service.” When we see that, we’re not going to comment. We’re not going to say anything. It’s great that hearing instructors and interpreters sign, but if they do something with the language, most of us typically have to take what they give us. There are a lot of layers that come up with that. They never think about the other perspective and the accessibility and the power dynamic that’s there.

And another layer that is important to add is with Black and Indigenous and people of color and those who are queer and trans—again, there’s this colonialism that happens where white Deaf people have that access and that privilege to education, to financial privileges. They take over language for the rest of the marginalized groups in the Deaf community in so many things. For example, Black ASL, so much research is not available. We don’t have enough research. There isn’t more information about that language development. But you see so much research related to white ASL. But we don’t look at all of the other cultural components from the Asian community, from the Mexican community, from Indigenous communities. So there’s this colonization that happens from the hearing white Deaf perspective that interplays with everything there. And then the Deaf community—that latches on from the general society, not just onto the Deaf society. So we experience that micro oppression or that macro oppression even within our context and our experience.

ttl 36:32

There’s so much to think about there. Thank you for being so vulnerable and talking about your lived experiences as Deaf interpreters navigating a white-dominated, white-supremacist world. And I’m curious to know what that advocacy looks like right now. Do we see that changing? I’m curious because publishing, for example, is more white than it used to be ten years ago. In the Deaf interpreting community, the ASL interpreting community, what do you think it’s going to look like in the next few years? Will it change?

XCE 37:37

I would say there has been change. Speaking just from a governmental base—there’s been more and more awareness and understanding of the process of asking for interpreters and getting interpreters. It’s a slow and gradual change, but it’s definitely happening.

The problem is that there still is a push that people are not willing to take on. They’re kind of like, “Oh, you know, my job is done. I’m good.” But we need to continue to push this forward and advocate for these changes. Because I’ve noticed it happens in the hearing community, like Rom mentioned, it’s hearing interpreters who got their job and they feel like they’re done. They feel that they can speak for us as a part of the Deaf community, and that’s not the case.

And we have to challenge that and remind each other that when we work in the interpreting field, we are public servants. Point blank. The beliefs of some interpreters are a little bit different. They have an entitled mindset that they have their job and it’s their right and they have the right to say these things. But in reality, we’re public servants as interpreters. Same thing as police, firefighters, first responders—anyone in the public sector in that type of area is a public servant. That’s what we’re labeled as, but it’s just the concept. I’ve noticed that there have been some changes, and I’m hoping that it continues to push that way.

As for Deaf interpreters specifically, I’m starting to see more and more and more Deaf interpreters. And so as an advocate, it is also my job to empower consumers to say, “I need a Deaf interpreter.” At the end of the day, we’re service based, so therefore the consumer needs to be able to request that. My big challenge with advocacy right now is the educational aspect of it and the power dynamics, that we just need to have appropriate accommodation. We just need proper accommodation.

RN 40:20

Yes, I agree. I do see change; it’s starting more and more. We saw before that the shift was happening because we were being more vocal. We were being more expressive about interpreter error and our expected experience and the challenges that were happening. And now we see that pushback from the community—

XCE 40:52

Yeah, that backlash.

RN 40:54

Yes, the Deaf community is saying that because often—if we hurt the ego, there’s a hearing person and hearing interpreter that’s there, and they don’t want to work with a Deaf interpreter. Their thought might be, “Oh, I’m not good enough,” or “I’m not good at my job,” or “I can’t, I’m not a good sign language interpreter.” And the reason why the Deaf interpreter is there is to advocate, to create accuracy and full access for the client. And so putting together your hearing experience and my Deaf experience is to make sure that we work together toward the goal of creating that accessibility for the client. So it’s sad that often I have to work with people and there are a lot of filters, or that a lot of the time people make hearing-based decisions, and Deaf people aren’t involved in the process.

For example, I recently applied for a job and went through that whole process. The person who was assigned to analyze my language skills and see if I would be appropriate as an interpreter, that person was hearing.

I’ve noticed in the hearing world, people generally deem your worthiness based on your educational background. Hearing people tend to say, “Oh, if you have a degree, that means you’re an expert in that field.” And in this case, Gallaudet University, being a Deaf university, if you have gone to that university and have a degree, you’re deemed to be an expert. I do have a degree from Gallaudet. And so I went into this interview with this person who was supposed to analyze my interpreting skills, and they said, “I’m gonna go ahead and pretend to be a Deaf person.” And I thought to myself, “Why can’t you use a real Deaf person? Why do we have a hearing person acting as a Deaf person instead of just having a real Deaf person in there?”

And taking a look at their language skills, this hearing person acting as a Deaf person, their language skills in ASL did not fit what a Deaf person’s language skills would be. So there’s just a lot of little things that were in that interview that were really annoying. Then a huge negative came up regarding the word grassroots. The word grassroots typically has referred to people in activism and movement spaces. The people rising up. But ironically, in our community, for some reason, hearing interpreters tend to interpret that word to mean something that’s derogatory—oh, a Deaf person only having ASL and not having skills in English or someone who struggles with English or something of that nature. That’s how hearing people look at Deaf people. “Oh, that’s a grassroots Deaf person” as to put them down instead of what it really has been traditionally used for.

So this hearing person pretending to be a Deaf person signed to me, “Oh, yeah, grassroots.” She literally signed the word grass and the word roots instead of the sign that has been created by Deaf people for grassroots. So this hearing person has power over me and could say, “Oh, this Deaf individual’s not ready to become an interpreter,” and everybody would believe them, as a hearing person, because they’re the one in the power to say whether or not I could have this job. People would just believe them, when this person couldn’t even sign the concept grassroots correctly. It’s a multi-layered situation.

XCE 44:19

It’s gatekeeping.

RN 44:20

They create this gatekeeping in the grassroots movement. So hearing people are creating gatekeeping and barriers in the grassroots movement for Deaf people, instead of including us and letting us be at the forefront and advocating and creating that movement and push for ourselves.

ttl 44:44

Thank you so much. Y’all are amazing. One of my last questions is with your histories: Did you grow up in multilingual households and does that show up in your work?

XCE 45:23

I was raised in a multilingual household. My mother only spoke Spanish, and my father spoke English and Spanish. As for my sister, she spoke Russian, Spanish, and English. Also, she signed as well. So I was raised in a house with multiple languages. At the same time, it was a huge challenge, because after I graduated high school and I was out in the real world, the ability to continue with my language development just went away, because there was less contact with my family, less time with people who I normally socialized with. But now as I’m getting older, I’m starting to realize how important it is to continue to socialize with people who speak the same language and are able to maintain that linguistic development. That’s extremely important for me.

RN 46:31

In my household with my family, my parents were refugees and their first language was Cambodian. Unfortunately, for many Deaf people, we typically don’t have access to sign language. Everything is spoken. So I didn’t have that access. But I could see some things about our culture. I’m the last child, so that exposure was a little bit different, being the youngest. All my brothers and sisters, especially my oldest brother, would really advocate for me. They taught me about our culture and the world and educated me on how to navigate for myself. Through that space of academia and community, I was able to learn and learn more from my family about how to keep my culture. And if it wasn’t for my siblings, I probably would have lost that because my parents couldn’t communicate with me. So they couldn’t expose me to our language and explain why we have these cultural nuances or our background. So I had access to culture, but not language, unfortunately.

And so the other reason why I was motivated to pick up languages, for example, learning LSM language, Lenguaje de las Manos. Many people have a misunderstanding that ASL is one sign language and that it’s universal. To those people, I would ask, “Well, is there a universal spoken language?” And that’s not the case. So why would you have this expectation with sign language? There are many different sign languages. Each country kind of has their own. There are nuances even in those regions. So there’s that similarity to language. That’s basically how I started my work and picking up language.

XCE 48:44

Yes, to add to what Rom mentioned—it’s not only the Deaf interpreter, but it’s also other things like technology popping up: YouTube, Facebook, Instagram. Everything blew up in that way. And so I was able to learn from other Deaf people and able to get their signs, as well. I learned from a person who moved here from India, and I was able to learn some Indian Sign Language along with English. So I continued to add to my overall linguistic tool belt. Families do incorporate some ASL but also do some home sign as well, as a form of communication. Long story short, the communication that we can have with Deaf people all over the world because of the advent of social media has definitely been a net positive for us. And it has really helped even in interpreting for different situations as well.

ttl 49:56

Thank you so much, I so appreciate our conversation and how open you were, how rich it was that we got to talk about anti-imperialism and how to fight white supremacy and how it shows up in the Deaf interpretation community, how it shows up in the Deaf community. The gatekeeping, the layers that everyone experiences. I’m realizing it’s so pervasive.

My last question is: Do you enjoy poems? Do you enjoy language? I’m curious what makes you happiest working, what makes your heart flutter while you’re doing this work?

RN 51:32

I enjoy both. I love poems. I write poetry myself sometimes. But it’s a challenge creating that translation between English and sign. But I do enjoy poems. I really love being immersed in signing poems, signing songs. I love being involved in creative endeavors like that.

XCE 52:08

I used to write poems myself a lot. But, I have a little bit of dark poetry. So I stopped doing poems. When it comes to linguistics and interpreting, I would say that often people ask me, “What’s the one thing you enjoy the most?” And for me, it’s the challenge. I love everything. I love the challenge and being able to work through it.

I started going back into poetry a little bit, but I’m more focused on poetry through culture. The cultural lens and the intersection between poetry and culture, how both of them can meet each other. And I don’t want poetry based on white people; I want it to be culturally rich and have that rich connection with my culture through my poetry. And explaining now how I grew up Deaf and having that problem of having an identity and developing culture—so for me, this is about a reclamation of my culture, and I can do that through the lens of poetry.

RN 53:32

Same thing for me. It’s always trying to figure out how to reclaim my identity. Because in Deafness with language, it’s so complex. In general, white people have a lot of advocacy for disability and mental health. They have resources there. And for some reason, for Black and Indigenous and people of color—I’m speaking for myself, in general—something I’ve noticed as a similarity is that we have a strong negative connotation with mental health and expressiveness. We have to say that everything’s fine and be so stoic. We kind of shut everything behind that door.

And so I have to pick. Am I Deaf or Cambodian? And in the Deaf community, they’ll say, “Oh, you have to emphasize your Deaf identity.” But I put my identity markers with Deaf last because I want people to see me first. People do see a visualization of who I am first, so when they meet me, “Ok, okay!” And then they realize that I’m Deaf later. So it’s after we’ve had that interaction and they have that visual cue that they notice my Deaf identity. So I have both; I can’t pick one. That is just my identity. It’s not singular. Again, with intersectionality, it means that we recognize that we have many different identities. And we’re not just recognizing the marginalized parts. We recognize all of the different conflicts and the sometimes triple, quadruple oppressive experiences that we’ve had because of those multiple identities in our intersectionality.

ttl 55:40

Y’all are amazing. Thank you so, so much. I feel like we could talk about this forever. And I want to pick your brains forever. You said such rich things. And I think that these are all things that we always talk about at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop. I’m so happy to have been in the room with the two of you to talk about these things, these complexities. I don’t think the conversation with the Deaf interpreters will stop here from AAWW. We appreciate everything that all of the interpreters do and love working with Pro Bono ASL. This was an immense pleasure to be in the room with you to hear what you had to say about poetry and language. And as a poet myself, it excites me. It makes me want to go and write and write and write.

RN 56:56

Thank you, again, for giving us the opportunity to have a seat at the table. To have the opportunity to share and be vulnerable and talk about our experiences. In English they say, “Don’t talk the talk, we walk the walk.” That’s what we want to do. We want to create that change and have people actually doing the work.

XCE 57:38

Yeah, I agree with what Rom just said, and I give many thanks. This is an extremely important discussion, and I feel it’s not going to be this one time. It’s important to keep this exposure going and keep pushing forward.

ttl 57:55

Agreed. Thank you so so much, Xgamil and Romduol. And huge thanks to our interpreters, Gregorio and Jared, always such a great pleasure to have you share space with us. And to you, our community watching, thank you for joining us, and we’ll see you soon, and we’ll keep these conversations going.

This piece is part of the “Listen to My Hands” portfolio, cosponsored by the Poetry Coalition for its 2022 theme “The future lives in our bodies: Poetry & Disability Justice.”