Poet Don Mee Choi discusses the myth of fluency and what happens when translation is allowed to be hysterical

June 16, 2015

Don Mee Choi is a translator of feminist South Korean poet Kim Hyesoon—most recently of Sorrowtoothpaste Mirrorcream (Action Books, 2014), which was shortlisted for the 2015 PEN Award for Poetry in Translation. The author of The Morning News Is Exciting (Action Books, 2010), Choi has received a Whiting Writers Award and the 2012 Lucien Stryk Translation Prize. Her most recent works include a chapbook, Petite Manifesto (Vagabond Press, 2014), and a pamphlet, Freely Frayed, ?=q, Race=Nation (Wave Books, 2014). Her second book of poems, Hardly War, is forthcoming from Wave Books in April 2016.

In the following interview with Margins Poetry Editor Emily Yoon, Choi talks about the failing and afflailing tongue, the position of history and politics in translation, and the American tendency to insist on joy, among other things. Choi proclaims, “If you’re not already, you’ll soon be a junkie of Kim’s adorable, often bloody, rat, cat, pig, hole allegories of patriarchy, dictatorship, neoliberal economy, and neocolonial domination.” Read two of Don Mee Choi’s translations of Kim Hyesoon’s poems in The Margins. And look out for a series of essays and short reflections on Kim’s work later this week.

Emily Yoon: This is not the only collection of Kim Hyesoon’s that you’ve translated; how did you come upon Kim’s poetry?

Don Mee Choi: I first came across Kim Hyesoon’s poetry in an essay written by Kim Chông-nan, a Korean poet and feminist literary critic. The paper was given to me by my longtime mentor, Bruce Fulton, who has produced many great translations of modern Korean women’s fiction with his wife and co-translator, Ju-chan Fulton. In 2000, when a few of my translations of Kim’s poems were accepted by Arts & Letters, Bruce kindly passed on her home phone number to me, so I could ask for permission to translate.When I called her, her renowned playwright husband, Lee Kang-Baek, answered. He said that Kim Hyesoon was not home and that, even though she was his wife, he had no idea when she would be home. He was being cheeky, of course. It was his way of letting me know that Kim Hyesoon is a not a conventional Korean woman, which is to say that he was not a conventional Korean man either.

They are a radical husband and wife who wrote and survived several decades of oppressive, U.S.-backed military dictatorships. The second time I called, Kim Hyesoon answered and she almost yelled at me for not contacting her when I told her that I had found several of her books when I was in Seoul the previous year. When we finally met in person for the first time in 2001, we found out that we both knew Jeong Yu-jin, an activist involved in issues related to crimes committed against women by the U.S. troops in South Korea. Kim knew Yi through a feminist organization she belonged to, Another Culture, while I knew Yi through International Women’s Network Against Militarism. My encounter with Kim Hyesoon’s poetry was not a chance encounter; it was already in the works on a collective level.

What is it about her work that is especially attractive to you?

Intensity. Over the years, I’ve become a junkie of Kim Hyesoon’s intensity while reading and translating her poetry. But before I was hooked on Kim’s work, I was hooked on the work of avant-garde poet/writer Yi Sang, who daringly punned vulgar swear words into his poems right under the noses of Japanese colonial officials. I’m hooked on Kim’s seemingly benign, apolitical cooking poems that she wrote during the dictatorship and her cutesy word plays on gender-role expectations (“Double p—How Creepy,” for instance). If you’re not already, you’ll soon be a junkie of Kim’s adorable, often bloody, rat, cat, pig, hole allegories of patriarchy, dictatorship, neoliberal economy, and neocolonial domination. What’s not to like?

Curiously enough, there is a phrase exactly like this one—“What’s not to like?”—in Korean, too. As a child I would encounter it whenever I would complain about things to my mother. She never hesitated to straighten me out, saying, you are alive aren’t you, and not starving? So, what’s not to like? It made perfect sense when my mother, who had survived the Korean War, would use the phrase. But what was puzzling to me was that this same phrase also existed in the U.S. It just didn’t seem to fit with its history. It seemed even more puzzling to me that the exact same phrase would feel like a mistake. What could it be then? A translation misfit.

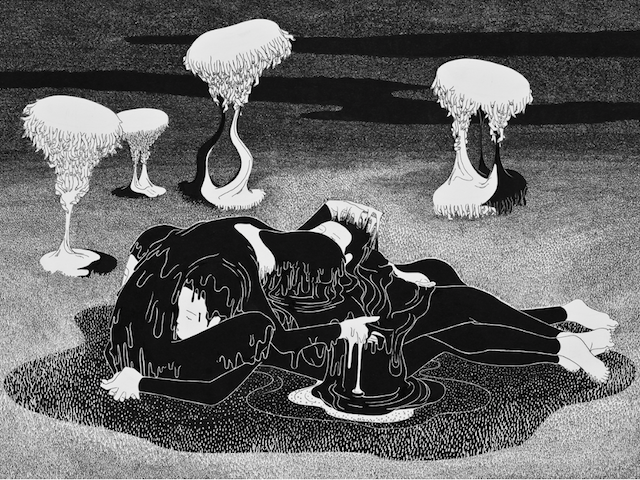

Once in a while I get an uncontrollable urge to shatter the myth about the idea of fluency in translation. In my world of translation, fluency doesn’t exist. My history is a misfit. Barthes observes in Camera Lucida (translated by Richard Howard) that “History is hysterical: it is constituted only if we consider it, only if we look at it….” When translation is allowed to be hysterical, language becomes askew as with Tawada’s translation double, Kinoko-san in Where Europe Begins (translated by Susan Bernofsky and Yumi Selden):

“That person, you know, the one whose name I flailed to catch, now what was she called?” I tried saying. Even in the dark I could feel Kinoko-san bristle with excitement at the word ‘flailed.’

The next morning, Kinoko-san, her face striped in the light coming in through the blinds, opened the large smile in the middle of her face, and murmured, “Well, I do believe I’ve finally afflailed.”

It seemed as if I had finally afflailed, too.… I would say, “I’m going out for a bit. I mustn’t just sit at home afflailing away the day.”

I’ve come to notice that there are certain tics already embedded in Kim Hyesoon’s language in All the Garbage of the World, Unite! They might be tremors or ripples of some sort. Whatever they are, I felt them and translated them: “waddlewaddling,” “cacklecackled,” “stiffstiff,” “staggerstagger,” “limplimp,” etc. History in translation induces a frenzy of misfits, fits, and tics. They happen to me too, usually at airports and Immigration and Naturalization Services. Law is determined in its frenzy against the ill, the immigrants, children or not. Nevertheless, the hysterical is what captivates me most about translation.

What is the greatest challenge when translating Kim Hyesoon’s work?

I think Kim Hyesoon spells out best what the challenges are in her interview in Sorrowtoothpaste Mirrorcream: “The Korean language has countless variations in adverb, adjective word endings, multiple onomatopoeias and mimetic words, and through them the Korean language is vibrant with ironies and fluid in syntax. And it’s a phonetic language rich in history, which allows for possibilities of rhyming through countless homonyms that are closely or directly related. In translation, it becomes difficult to reveal all these aspects of wordplays in Korean.” I am very fortunate to be able to consult her on these challenges, and they are also what keep us connected often via email. And, yes, we also complain about things.

When translating from Korean to English, what is the greatest joy?

I am terrified of English. And because I have lived outside of South Korea for a long time, I’ve become a foreigner to Korean as well. In other words, I am a failure of language in general. So joy does not come to mind easily when I think about translating from Korean to English. I also associate joy with ‘Joy of this and that’ I saw and heard everywhere when I first came to this country, including green-colored JOY detergent. It was the first dish soap I used after my arrival. I wondered, even in my state of devastation having just separated from my family, why this nation was so obsessed with joy when it causes so much misery all over the world. I was not opposed to joy; it simply wasn’t what I knew best. What I knew best were the poor and the orphans who came to our house daily to beg for leftovers, the marshal law, curfews, threats of war on the Korean peninsula, student demonstrations, torture, trauma, separation, homesickness, and so forth.

I arrived in the U.S. already knowing enough English, so that was not the problem. The problem was that I was constantly mistranslated even before I could translate. Once, someone who appeared to be very nice told me that she thought all Chinese people were always smiling and were happy. I’m translated into Chinese even though I rarely smiled nor was I particularly happy for that matter. Then another time, out of nowhere (translators do tend to appear out of nowhere), someone translated me on the spot—a bold move, a skill I have yet to acquire. He said I was afraid. That is pretty close, I thought. But I quickly realized he was thinking of something else.

Joy of______. This is the crucial part of translating from Korean to English—filling in the blank. How I go about resisting with what and how the blanks get filled is part of my translation work. I’ll admit it. Resistance gives me much joy.

I feel tremendous joy when Kim Hyesoon’s work is enthusiastically received and published by amazing small presses: Zephyr, Tinfish, and Action Books. It’s joyful to learn that Kim Hyesoon has a following in U.K. And it’s immensely joyful to read all the insightful reviews of Kim Hyesoon’s books by wonderful writers and scholars who are so open to reading and experiencing Kim’s poetry in translation.

During a reading at Smith College in 2003, Kim Hyesoon said that, while she was driving in the rain, she happened to listen to a poem and thought, what an interesting poem. (Poems are regularly broadcasted on radio in South Korea.) Then she remembered that it was her poem. This story made me think about what my father used to remind me of—that forgetting oneself is the best medicine for anxiety or fear. That is what his highly respected Korean psychiatrist prescribed to him when he suffered from PTSD. My moment of greatest joy is when I come across a poem by Kim Hyesoon and think, what a great poem and forget that it is my translation. Forgetting is a salve for my afflailing in particular.

Although Kim says she had to “reinvent the mother tongue” due to the patriarchal nature of Korean poetry, she seems to have been especially influenced by the modern Korean poet Han Yong-un. Many of his poems in the feminine poetic voice are about the lover’s back (as he leaves) and partings. Also some think that “sorrow” is an unavoidable theme in contemporary Korean poetry since modern Korean poetry from the colonial era has become the main poetic canon in Korea. I think that Kim’s sorrow and voice are uniquely hers, but also distinctly Korean. How do you think this notion is asserted in the translation (or do you disagree)?

I think Kim Hyesoon’s interest in early modern poets like Han Yong-un and Kim So-Wôl is not that they wrote in the feminine poetic voice but that they adopted such feminine voice. Kim mentions in the appendix that she is also interested in the feminine poetic voice in the poems “written in exile by men expelled from their government positions by the king.” As aristocratic men they did not have to adopt the subservient tongue that was primarily designated to women and lowly outcasts such as shamans. So their choice was historical. I tried to point out in my preface to Princess Abandoned that Kim’s analysis and use of the shaman narrative in her criticism show Kim’s alignment with, not just the feminine voice or the inversion of voices, but the expelled voices, the poetics of expulsion, including Joyelle McSweeney’s theory of the Necropastoral. I think Kim’s long poem in Sorrowtoothpaste Mirrorcream, “I’m OK, I’m Pig,” is a magnificent work of poetics of expulsion. The squealing pigs “qqqq”—these are the cries of expulsion:

They cry in the grave

They cry standing on two legs, not four

They cry with dirt over their heads

It’s not that I can’t stand the pain!

It’s the shame!

Inside the grave, stomachs fill with broth, broth and gas

In 2012, Kim was invited to the largest gathering of poets, Poetry Parnassus, held in London. In an interview with SJ Fowler, when asked how she felt about being a representative of her nation and its poetic culture, she answered: “I am a poet from the nation called The Poet, Kim Hyesoon.” During the festival, Casagrande, Chilean arts collective, dropped 100,000 poems (as oppose to bombs) from the sky, from a helicopter, and Kim Hyesoon’s poem, “Red Scissors Woman,” was among them. That was a great moment of collective sorrow.

When I interviewed her a while back (in positions: east asia cultures critique, Vol. 11, No. 3, 2003) Kim said that she was most influenced by and identifies closely with the tradition of muga, shaman narratives. As a translator, I do my best in my role as a medium of her poems. Whatever sorrow and wounds in Kim’s poetry are transmitted through my afflailing tongue. A translator’s tongue is inherently sorrowful. It’s an organ of arrival and departure. My tongue is an expelled tongue.

What is the relationship between your creative work and translation?

I write my poems with the same tongue that I translate with, so my creative work and translation are closely intertwined. Translation often sticks its tongue out when I write my own poems. It’s one of those unavoidable tics.