An introduction to the folio, featuring 누가, 네, nhân vật, con, chanh, …, 그 (kû), 님 (nim), 형 (hyeong), tôi, em, chúng ta, một ám ảnh, I, [ ], [who?], 我 (wo), kau, aku, dia, ia, you, and a selfsame similarity

March 6, 2019

The Pronoun is the category of little words entwined in big discussions of identity and representation. As the pieces of language symbolic of who is seen, legible, and recognizable, The Pronoun holds the space of a subject and to some extent, the limits of subjectivity itself.

As rooted in the mud of both ethical and aesthetic concerns of language, when charged with the complicating concerns of translation, The Pronoun takes on an even broader capacity to press on thinking’s vocabulary. Because who I am not only varies according to who you are, relationally, but who we are (inclusive or exclusive) also varies according to which languages we are speaking, more questions open. What subjectivities and legibilities exist outside of this particularly fraught frame (in English)? What spaces are there in [insert your language] for an existence to be possible? What constraints and impositions direct perception and into which dark corners? And what kind of ambiguities and silences are left alone to bask unbothered in the fields of unarticulated being?

Ways of speaking to and understanding each others’ selves are specific to each language world. In this folio, you will meet some of the language worlds within Vietnamese, Korean, Bahasa Indonesia, Chinese, and a mythical language composed of only verbs in the Philippines. And you will meet the shadow worlds of English that weave in and out of all of these. What is special (to me) in encountering these worlds wrapped up in concerns for The Pronoun is how even the most fundamental categories of being can always be otherwise—how the room one is allowed or one carves for oneself can expand and contract with a word, the movement and tensions of which leave (me) slightly changed (in English) as a result.

To encounter expressions of gender and queerness, the necessary innovations away from a precise social mapping in the work of Ly Thuy Nguyen, the generosity of the undisclosed in Sora Kim-Russell and the undifferentiated in Norman Erikson Pasaribu with Tiffany Tsao, to sense a (national) body’s fragmentation and togetherness in the poetry of Vũ Thành Sơn, autonomy and its illusions in Mu Dan with Emily Goedde, sameness and its illusions in Dominic Paul Chow Sy, the poetic function of the second person in Ly Qingzhao with Jenn Marie Nunes, and the poetic dysfunction of the second person in Kim Hyesoon with Don Mee Choi—to see these elements across languages is not to stare in awe at the differences between ‘here’ and ‘there’, but perhaps rather to feel the something radiating from outside languages and to step just a bit closer into that warmth.

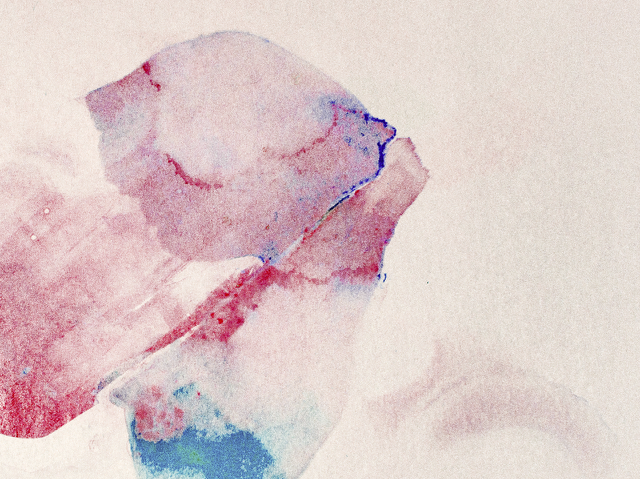

And in imagining just what The Pronoun might look like outside of language, blobs of color began to inhabit my mind. The artwork that accompanies each text in this folio is from the hands of artist and designer Emma Lu. From discussions about how the subtleties of relationships and identities could be visually represented, Emma has created a series of amorphous beings in which touch is inevitable. In the words of the artist:

“Monoprinting as a technique is probably best described as volatile:

as ink and oil are directly painted or collaged onto the printing

plate, a unique monoprint cannot be reproduced. Naturally, for

someone who takes Photoshop’s undo functions for granted,

moving back into this analog medium paid its price in sweat and

anguish. This quality also allows for immense flexibility in regards

to applications of color, enabling inks to bleed, smear, layer, and

collide with each other before they are pressed onto paper. As such,

each accompanying image in the folio is not only the sum of unpredictable

crises but also a number of happy accidents.

I was interested in reworking my relationship to this (frustrating)

medium because of the possibilities it offered in articulating

relationships between colors, and by extension, the complex

relationships that I was tasked to translate from the textual to the visual.”

***

I would like to extend a heartfelt thanks to the writers, translators, editors, and friends who made this folio’s call for submission live in numerous languages: Nhã Thuyên, Maung Day, Fan Wu, Mui Poopoksakul, Norman Erikson Pasaribu, Hafiz Hamzah, Hao Guang, Joshua Ip, Allison Markin Powell, Noel Pangilinan, Muna Gurung, and Jyothi Natarajan. Thank you to all who considered the call and shared your thinking and feeling into these pieces of language. And thank you, you, for inviting these pieces into your reading life.

With hopes that the poetry, fiction, essay, and conversation of this folio will energize more asking and listening into more possible subjects, TLP invites you to The Pronoun. We will be unfolding the following index of beings over the course of the next three weeks.

—Kaitlin Rees

The Pronoun folio: a Transpacific Table of Contents

The Implicit I: Contesting Ambiguity in Korean Literature—Within a grammar simultaneously specific and “vague”, Sora Kim-Russell finds herself, as translator, among the hidden subjects of Korean literature and questioning how to frame relationships that refuse English framing.

Pronouns: 그 (kû), 님 (nim), 형 (hyeong), …

The First and Second I & Missing Person | Dua Aku & Orang Hilang—In the space of defamiliarized subject(mother)hood, Cyntha Hariadi’s poetry, with translation from Bahasa Indonesia by Norman Erikson Pasaribu, is a wild reclaiming of the female I.

Pronouns: kau, aku

Heart’s Exile, Day Forty-Seven | 심장의 유배, 마흔이레—Kim Hyesoon’s poetry is seeking you: a space where the no-longer-i makes a possibility of poetry. In this excerpt from Autobiography of Death translated from Korean by Don Mee Choi, a window opens into the pronoun choices of death.

Pronouns: 누가, 네

Everything is here but the one who matters—In a selection of ci by Classical Chinese poet Li Qingzhao, translator Jenn Marie Nunes shifts the historically gendered and biographical readings of the poet to return to the intimacy and distance of “you”.

Pronouns: you

Some Quiet Conversation—Rooted in the conflict between the (historical) collusion of Philippine politicians and academics to justify dictatorship, Dominic Sy’s fiction embraces the seemingly endless generative abilities of Austronesian languages and the shadowed presences they can produce.

Pronouns: a selfsame similarity

我 [ ] I: Translating the Subject in Mu Dan’s “我”—Acknowledging the space between [Chinese and English] languages as a generative emptiness, Emily Goedde lingers in the echoes of her I and Mu Dan’s 我, asking what knowledge is made in the crossing.

Pronouns: I, [ ], [who?], 我 (wo)

Safe sex and Exile | Tình dục an toàn và Lưu vong—When shattered and dispersed, the body and language remake home in each other in the poetry of Vũ Thành Sơn, with translation from Vietnamese by Kaitlin Rees.

Pronouns: tôi, em, chúng ta, một ám ảnh

Does a face need a mask?—In a discussion on Bahasa Indonesia in English, Norman Erikson Pasaribu and Tiffany Tsao converse on the translation of nonbinary beings and what can be done in the limited space a language provides.

Pronouns: dia, ia

Fruits of the Future—Taking on the insufficiency of [Vietnamese and English] language as it exists, Ly Thuy Nguyen outlines the unlearned and the unknown as spaces of innovation and models of imagined queer futurity.

Pronouns: nhân vật, con, chanh