These writers elegize and scrutinize the liminal spaces between taste, smell, and image, between individual truth and collective meaning-making

June 6, 2022

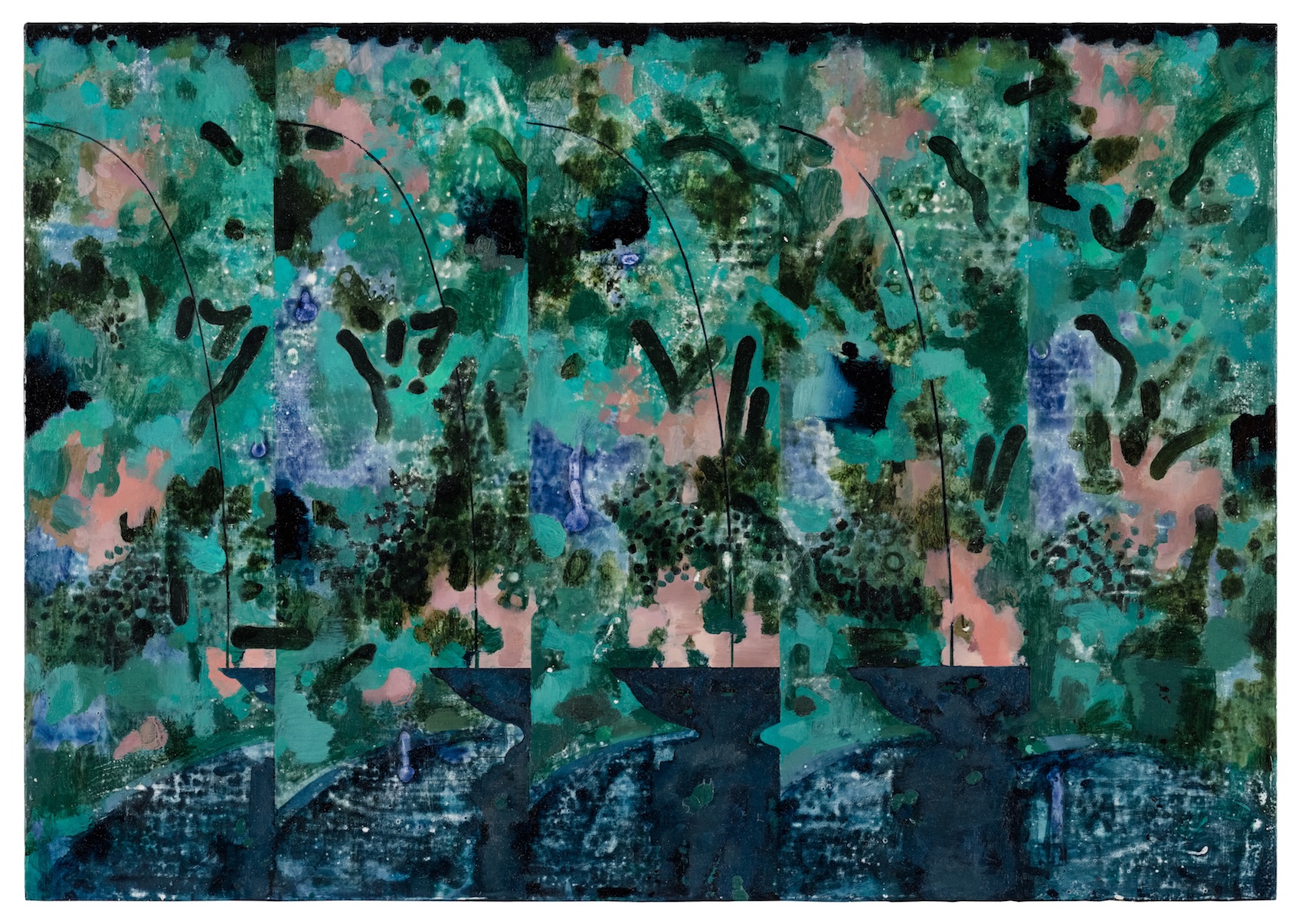

This editor’s note is part of the Wine notebook, which features original art by Su Yu-Xin.

Lyrical writing provides a kind of alchemical prolonging of life to its subject, as wine provides to fruit or grain. Both act as living vessels of the history, memory, and care that their makers put in, and that we, as readers and drinkers, simultaneously filter through our own personal histories and sense memories. The body and the bottle—we siphon off substances and place them inside, hopefully to compound and synthesize, with the intention of pouring them out on a later date, on a night marked by safety and communion when what has long been stored, growing luxurious or cloudy or wild, is reintroduced to the bald truth of oxygen.

Intoxication, with its dangers and allure, is magnetic—how it can alter our perceptions about ourselves, our relationships, our values and worth, and its propensity therein to reveal the structures of power at play. In this special notebook on the theme of Wine, thirteen writers add remarkable texture to the lyric landscape of perception.

These writers elegize and scrutinize the liminal spaces between taste, smell, and image, between individual truth and collective meaning-making. The speaker of Somi Jun’s poem, “Please, waitress,” navigates the claustrophobia of being exoticized by sake-drinking patrons around the time of the Atlanta spa shootings. “Sake develops with exposure to oxygen, so as time goes on, the flavor will change . . . The flavor changes, it changes,” repeats the speaker to themself, becoming an incantation for future social change and equality. The speaker of Sarah Aziza’s essay “Terroirs” similarly navigates a landscape of influence and exile: “Later, I needed the concoctions F poured to quiet the things that grated, grew wilder each year—the confusion of being part-white in an Arab country, part-Arab in an expat world.”

Among its enticements, wine can serve as nostalgia’s brew, as a sort of truth serum. Time can be perceived as layered, palimpsestic. A character who is guarded while sober might unwind enough in order to tell difficult stories or truths, as in Xiao Yue Shan’s poem “after country,” where a night of drinking baijiu on a trip to the speaker’s father’s country of origin leads to “liquor cur[ing] honey along the throat . . . harvesting stories of country from my father.” Aside from the promise of intimacy, there can also be great pain to expressing truth within a family, as explored in Arah Ko’s sinuous poem “Vampire Plants Talk to Their Victims While Drinking,” “The vines of the vampire / plant swell around words // we don’t say: / parasite, addiction, / sister witchweed, cousin // broomrape, limbs tangled…”

In Suphil Lee Park (수필 리 박 / 秀筆 李 朴)’s translation of Kim Hoyeonjae (김호연재 / 金浩然齋)’s poem “生涯 | 생애 | Life,” “the entire life / Of a nameless thinker” touches on an endless, yet simultaneously momentous experience of life, a perspective that warrants for the speaker “indulg[ing] … in a barrel of wine.” Even the process of Park’s translation, from Hanja (Old Korean) into Hangul (modern Korean) and then English, mirrors this accordion-like experience of time.

In Lio Min’s prose piece “Revel Nation,” a reservoir functions as both the piece’s setting and the shape of its emotional container, a basin of suppressed memory that overflows, fueled by drinking among friends and the all-commanding atmosphere of an outdoor rave. The veil thins between the speaker’s waking world of young hedonism and escape, the world of dreams, and the world of the dead and those who grieve them.

Several pieces in this folio touch on how wine’s potency can also allow for the excavation and unfurling of desire. Both Janelle Tan’s essay “Skin Contact” and my own piece “Tasting Notes” (selected for this notebook by the editors of The Margins) honor the archival nature of falling in love and committing to a vision of a shared life with another, as well as learning to tend to one’s own tastes and interests with equal patience, letting the self “open up” and “develop” just like a glass of wine. Cleo Qian’s poem “Locheequat” imagines the “fruit of the non-doing […] fruit of more life” in a sensuous summer ode to decommodifying pleasure.

In a religious context, wine is often associated with its transubstantiation into blood. In “Sandugo,” Vincent Tolentino collages together remembrances of the speaker’s Catholic upbringing, accounts of blood covenant ceremonies through history, and various identities and creation stories, including accounts of coconut wine drunk during Magellan’s colonizing expedition, that contribute to the soul of the Philippines. Jen Mutia Eusebio’s essay “Kinutil,” touches on the significance of coconut wine in Filipino history, but focuses on the dignity and the labor of Filipina women as the keepers of tradition, particularly of homemade elixirs and remedies that thrill the tongue and enliven the spirit. Wine serves as an epic, mythic catalyst to religious intoxication in Rebecca Ruth Gould and Kayvan Tahmasebian’s Persian to English translations of Khaqani Shervani’s poem “Morning Wine” and Saʾeb Tabrizi’s untitled poem.

The thirteen pieces in this folio are paired with original paintings by Su Yu-Xin, many of which were constructed with naturally occurring minerals, handmade pigments, and handshaped recycled woods and flax-prepared boards. With titles such as “Terrain Without Gravity,” “Dive (The Unriven Half),” and “The Sound of Cloud,” Su’s pieces are similar attempts at communication and translation between arrangement of image and form, and the various associations of texture, smell, and color, while acknowledging an expansive and plural approach to truth.

“Wine is steeped in a language that is coded and arcane, tied up with legal jargon and French techniques that only the privileged, monied few are able to decipher,” writes Miguel de Leon in his article “It’s Time to Decolonize Wine” published by Punch in June 2020. de Leon was writing shortly after George Floyd’s murder and responding, in part, to Black and POC wine professionals calling for more action by white people in wine; he further identifies that “the wine world’s culture of gatekeeping, racism and silence is antithetical to its true spirit,” which proliferates diverse human connection. In creating this notebook, I hoped to encourage writers to expand the imagination and language around wine. I am honored to have connected with the writers in this folio and to present their deeply felt and researched works, a wealth of stories and sensory experiences.